Childhood Memories

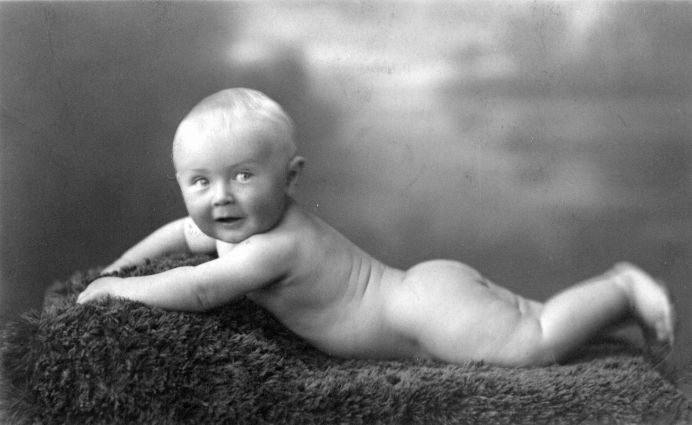

I came into the world around 4.00am on the 30th of January 1931. Mother said I was a difficult birth, and the midwife, who incidentally was Uncle Charlie's sister Molly, had to start me breathing by giving me brandy fumes! Mother and Dad, who married in 1925 at the Christian Meeting House in Rodney Street, put off the idea of a family for a few years, mainly because of financial problems. Just after they married, there was the Miners Strike of 1926, and, although Mother had been working at the weaving shed in Ashton-in-Makerfield, money was still tight. They started married life in a house in Frederick St. Ashton, and moved to 126 Billinge Road Pemberton after Great Grandad Foster died in 1929, because Uncle Harry Foster, who was living there, moved in with his mother at 128, as Great Granddad had died in 1929, leaving her on her own.

The pictures on Billinge Hill were no doubt taken using Dad's old Kodak.

It was one that folded flat and had leather bellows.

Billinge Hill those days was a favourite picnic spot and was usually reached on foot!

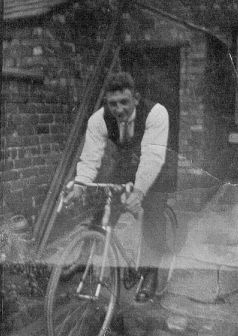

When I was born, Mother was 30 and Dad 31. Dad by then, had decided on a change of direction in his employment, and on my birth certificate, he is described as a "Master Poultry Farmer", a posh name for a hen keeper! He had about 600 laying hens on the pen that he kept, but there was no money in the game. I don't think that he stayed a professional poultryman for long, because my earliest recollections of him are as a pitman with a black face and clogs, as he came up the backyard with me on the saddle of his bike. The row of terraced houses where we lived was called "Hospital View", as it was facing the old Pemberton Cottage Hospital, and had been built by Great Grandad and Great Grandma Foster in 1898.

In the row lived quite a few of Dad's relatives, 128 housed Great Grandma, Dad's Uncle Harry, his wife Aunt Charlotte, and their son Harry. The two Harry's were always known as "owd 'arry and young 'arry".

Next door to us at 124 were Mr. and Mrs. Stretton. He was a surface worker at Blundells Colliery, and his wife was a very fussy woman. She always had to have things just right. It was said that before the war, Mrs. Stretton would ask the coalman to bring her coal that didn't leave much ash on the bars, as she didn't like to see it there! When the same question was asked after the war started, the coalman said, "Missus, you'll have to take what I can get now and be satisfied with it"

They had a married son, Ernest, who lived in Newtown near the Prince of Wales pub, Ernest was a bit of a snob, and had earned himself the nickname, "Mayor of Newtown" from those who knew him. He had a daughter Jean who sometimes came up to play with us. Ernest's wife, Mabel, was a sister to Wilf Sharrock, who had a cloggers shop in Goose Green.

Dad told me that when they were kids, they were playing in "Fishwick's Delph", an old quarry off Billinge Road. It was partially filled with water. They had been told the story in Sunday School of Paul and Silas's escape over the city wall in a basket, lowered by a rope, so they decided to re-enact it with Ernest in a big breadbasket! I don't think that Mrs. Stretton was best pleased about it! In this same water, John Stephens the landowner's son was drowned. The family, who at the time were living in Pemberton Cottage that is the old stone house with all the trees. They couldn't settle after their son's death and they moved away to Birkdale, near Southport. John Stephens owned most of the land in the area and gave his name to the industrial estate that is known as Stephens Way.

Later on, in the 1950s the quarry was filled in and the estate of Bold Street was built there.

At 122 were the Browns, Mr. and Mrs. Brown, Mr. Brown's mother, and their children, Arthur, Alfred, Stella, and later on, Helen. George, a coal dealer by trade, had a garage near Grandad's house, where he kept his coal wagon. When old Mrs. Brown died, a hearse complete with two black plumed horses led the funeral cortege. The old lady left a bit of money and soon, the Browns were the only people around to have an electric washing machine. I can see it now in their glass shed, a Servis machine with a paddle action. It was basically a drum on three legs with the motor and driving belt visible underneath it. As far as I can recall, there were no guards of any kind where the motor was. HSE would have had a field day today!

At 120 lived Dad's cousin, Edie King. She was a widow with three daughters, Hilda, Tizzie and Elsie. Her husband Frank King had died some years before I was born. They all lived with her along with her father, John Webster, who was Grandma Foster's brother. John smoked a pipe in which he burned a revolting mixture of dried coltsfoot and tobacco, and sometimes dried tealeaves!! John soled shoes to bring a bit of money in, and Eric Taylor, a cousin of mine, told me that John favoured a "clump" sole, where the new leather was nailed on over the old sole. I'll bet everyone felt that bit taller when they wore the shoes!!

118 housed great aunt Rachel, Grandad Foster's sister. She was also a widow, and her husband, Jack Gaskell had been a quarryman at the delph up the road, dying of silicosis. She had two daughters living with her, Millie and Edna. Millie worked at Lord and Sharmans, the slipper factory up the road in Campbell St. (During the war she joined the ATS). Millie only married late in life but during the war had a great time with the Yanks from Burtonwood and Ashton-in-Makerfield!! Edna was an usherette at the County Playhouse in Wigan. She broke her arm badly as a teenager and consequently had a problem with it all her life. It was never 100% and the work that she could do was limited. She also only married late, but didn't "fly her kite" like her sister. She married Jimmy Dodgin who worked on building sites, and they had 2 daughters, Pat and Kathleen. Aunt Rachel kept a few scrawny looking hens near to George Brown's garage, in a pen that was totally devoid of grass and the hens looked a miserable lot!

Next to them at 116 lived Mr. and Mrs. Walker, their son Jack, and two daughters, Beattie who was divorced, and Edie, who was about 6 years older than me. Beattie's two children, Norman and Marion Molyneux lived there as well.

To complete the row, Grandad and Grandma Foster lived at 114. We were quite a close knit little community in those days.

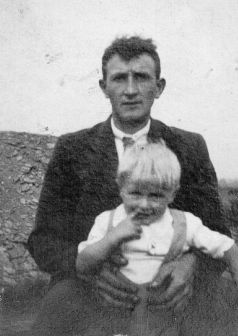

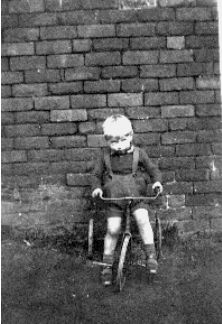

These photos were taken near the boundary wall of great grandma's house 128 Billinge Road. On the left, I was 2 and on the right, about 18 months.

Here is a pen picture of the families who lived in the row of houses below ours.

Next door to Granddad's, across the opening was the Culshaw family. Mr. Culshaw, his wife, and their unmarried daughter, Nellie. Mr. Culshaw worked at the Co-op, I don't know in what position, but he always wore striped trousers and a black coat and walked with little steps, a bit like he was walking on eggs! I never saw him in any other clothes, and he never got his hands dirty.

Mrs Culshaw had what you might call "pretensions" Ma said that she would get her housework done very early in the day, and then sit around the house wearing gloves, pretending that she had a maid to do the work! Nellie, the daughter, was a bespoke tailoress and a very good one at that. She never married, and after her parents died, lived on her own for a long time. She finally died from hypothermia, having fallen and, not being able to summon help, had lain on the floor for a couple of days. Edna's mother got the job of clearing the house after the death, and it was just like a time capsule, with all sorts of forgotten things hidden away in drawers. We even found a ouija board. I don't know if the Culshaws tried contacting the spirits, but we certainly didn't. It went into the dustbin!

Mrs Culshaw wore a dust cap and pretty longish dark clothes, I can visualize her now, there was a patch of grass outside their back gate and she was forever chasing us kids away. We hated her! In fact, when she died and Ma told me, I shouted out "Hooray, I'm glad!!" Ma was mortified at this and I was told off for saying it, but to me and the rest of my mates, she was just an ogress.

Next door to the Culshaws lived the Lawrence family, old Bill and his wife. They were a nice old couple who had 2 sons, Albert and Stanley, and Albert's daughter Elsie would come to play with Edna and Irene, Ted Twigg's daughters. Little did I know it then, but Edna and I were to be married later on! During the war, Lawrence's air raid shelter was erected in the backs and we would play in that sometimes. We had May Queens in which we dressed up with whatever came to hand. Silver paper salvaged from biscuits, crepe paper left over from Christmas. We had "trundles" covered in paper carried by "Trundle Bearers" Our hoops or trundles were usually old bike wheels minus spokes! It was all good fun at little expense.

The May Queen was a big event in those days, when the children dressed up in stuff that they either made or borrowed. "Silver paper" was used for the crown and bouquets made from crinkly coloured paper. This picture was taken in the "backs" of 106 Billinge Rd. Back row:- Edna, Irene Twigg. Stella Brown, Front:- Elsie Lawrence, Annie Hart.

In the next house, No 108 was the Stretton family, Ernest and Minnie, with daughters Annie, Nora, Nellie and Betty, or Sylvia, as she was sometimes known. I think that Ernest was related to the Ernest (Mayor of Newtown). Annie was in the forces during the war and married someone from down Cirencester way.

At 106 lived the Twiggs, Ted and Elizabeth, with daughters Irene and Edna. Ted and family came to live at 106 about 1935, because before that time, Roland Butts, the plumber and his wife lived there.

At 104 was the Birchall family. Old Mrs Birchall, her brother Jimmy, who I remember as a chap with fancy clogs, as they had brass nails all around the front of the sole. He was rarely seen without his cap, daughters Florrie, a sewer who never married, Kate, who had Downs Syndrome, and Nellie, who was mentally handicapped. I never remember seeing a Mr. Birchall, as he probably died before I was born. It was said, however, that he was a cousin of his wife and this could have accounted for the congenital defect in Nellie and Kate. Mrs Birchall also had a son Billy, who was married to Winnie, Tom Aldington's daughter, and a daughter Gladys, married to a man named Brooks, and they lived over on Worsley Hall estate, which had just been built to address the slum problem in Wigan. They had a son and two daughters; Jack, Jean and Kathleen. Jack and Jean came down to Grandma Birchall's to play with us all in the backs.

In the next house down the row lived Mr. and Mrs Tom Aldington, their daughter Annie, her husband Tom Stockley, and their two children, Alice and Arthur. Tom Aldington was an overlooker at May Mill, and Tom Stockley worked for Pooles Central Warehouse, which was a big shop in Station Road in Wigan town centre.

Living next door were Billy and Winnie Birchall, with their children, Tom and Winnie. Tom and Winnie were a bit older than me. Billy's wife, Winnie was Annie Stockley's sister. Billy also worked at May Mill.

Next door lived Mrs Melling (owd Margit, as she was known), her daughter Mary, who never married, and Mary's niece, Olive, who was the daughter of Billy Melling, the shoe shop proprietor in Newtown. Mary had an allotment behind the house where she grew flowers, raised a few chickens and had a couple of apple trees and she was always known to the children in the neighbourhood as "Auntie Mary". When I was around 12 years old, Auntie Mary wanted a chicken killed so she asked me to do it. I'd seen Dad do it many a time, so I knew the drill. Take hold of its legs in on hand, hold its head between the first two fingers of the other one, then pull and twist at the same time. I did this with a bit of apprehension, but I broke its neck as clean as a whistle. It was said of Old Margit, that when she wanted to kill a chicken, she would put its head in a noose and then run back into the house until the unfortunate bird was dead through strangulation!!

Next to them lived the Harts. Old grandma Hart, Jack Hart and his wife Jane, along with their daughters, Alice and Annie. The end house of the row was the shop, and when I was a small child, Ben Rollins, who was a brother to Tom, the coal dealer, occupied it. Later on, however, Jack Collier and his wife took it on and Mrs Collier told me many years later that I had gone into the shop, seen her behind the counter and said in astonishment, "Where's Ben?" After the Colliers, Harold Pouncey kept it until the war, and when he enlisted in the Royal Navy, the shop was closed and used for a base by the WVS, to stock blankets etc. in case of air raid damage.

This was the shop in 1938. The proprietor, Harold Pouncey is stood in the doorway. The Walking Day used to take place on a Saturday, prior to the "Field Treat" which was held in Winstanley Park, courtesy of the local Squire Captain Bankes. The girl with the posy is Irene Twigg.

Originally, when the shop was built, Old Margit lived there with her family, and I have a feeling that the three bottom houses and the shop were built by the Melling family, as the short street by the side of the shop is called Melling St.

I loved to wear my Dad's things when I was small, just like all other children do, and I was trashing around in his clogs one day, while he was at work, these being his "pen" clogs that he wore when going to see to the "flock". The clogs were discarded by the back door, and, when I heard Dad stop his bike by the back gate as he came in from work, I dashed out to meet him, tripped over the clogs, and gashed my chin on the step. There was blood everywhere!

Mam was going frantic; she picked me up, held a hanky to the wound, and carried me off to see Dr Oag, who was our GP. She had to hold me on her knee while he inserted two stitches, because in those days the doctor did everything, and was paid by the patient, usually at about half-a-crown (12.5p) a week. The doc had a collector going round to get the money in, and one of these collectors was John Lea, who was married to Grandma Foster's sister. He was known locally as "Johnny Blood" because it was said that he could get blood eawt uv a stone!!

I was poking around in the bureau one day, just like children do and I came across a doctor's bill, I can see the bill heading now, "Dr to Jas. Oag (Physician and Surgeon). Dr Oag invariably dressed in a dark blue pinstriped suit, with gold rimmed specs perched on the end of his nose, cigarette dangling from his lip, with the ash forming a long line before falling untidily on to his waistcoat, which covered his ample stomach. The waiting room in the surgery was really dismal. There were a few bentwood chairs to sit on, a hissing gas fire on when it was cold, a bare electric bulb for illumination, and on the mantelpiece was a rack full of various forms for the doctor to fill in, complete with an inkwell and pen. As there was a frosted glass screen across the bay window where the dispensary was, it was always dark and dismal looking. When we as children went to see him, there was no such thing as privacy. The surgery could be full but he would ask you in front of everyone there, "Now laddie, what's wrong with you?" in his Scotch accent. He was very brusque in his manner, but a good doctor nevertheless. When Ma miscarried a couple of times, he got her into the Christopher Home and attended her there. The fees at the time for the Home were 3 guineas a week, with Dad on around £8/week for wages, as a fireman or deputy underground.

It was said about Dr Oag, who was in partnership with a Dr Readman, at the surgery at Union Bridge, that a lady had gone to see him to ask for a "cough bottle". He mixed his own medicine in a dispensary situated in the bay window area of his surgery, as there was no such thing as going to the chemist with a prescription those days. When he had concocted the medicine, with the lady looking on, he said, "That will be half-a-crown," to which the lady said, "Eeh, doctor, it looks a lot for what you've just done" Dr Oag retorted "Go on then, mix it yourself." The lady said "Ah don't know heaw much fer t'put in" Dr Oag said "Well, that's what you're paying me for!"

There were other escapades that occurred before our Billy was born, some I can remember and either Mother or Dad told others to me, and one such event was the ride on the last tram in Wigan. Apparently, the trams were being taken off and replaced by a fleet of buses in 1931; I was around six weeks old at the time and was taken by Mother on the last tram to run in Wigan. The system was then broken up and sold off as scrap.

Years later, some tram track was still visible at Halfway House, before the setts were replaced by tarmac. Quite a few of the tram top decks were sold to be used as sheds etc, in fact, we had one in the hen-pen for a great number of years, being used as a cabin. It had plate glass windows that could be let down by means of a wheel at the front end under the verandah, worked by a ratchet and pawl system, so that if the weather was warm, the windows could be opened to let fresh air in. There were sliding doors made from oak and fitted out with brass handles. It was a very well made vehicle and was only demolished in the 70s. Dad had put the tram top on two railway sleepers, after fitting it with a floor.

Another of these tops was made into a caravan by Dad's uncle, Harry, who mounted it on to a horse-drawn lorry chassis. The interior was fitted out with an end bedroom, and a living room complete with a coal-burning stove for cooking and heating. It was in his pen for years, and at one time had someone living in it. When he sold up at auction, about 1946, the caravan was sold as well, and my mates and me were holding our breath, as the caravan buyer took down the fence to hitch it to a tractor. We fully expected it to fall to pieces, as it hadn't been moved for years, but it must have been well built, because it rolled away merrily, rattling on the cobblestones up Billinge Road, on its way to its new home.

This is a photo of a Wigan Tram. The top deck was taken off and sold to anyone who wanted it. It was one of these that ended up as a hen shed and another as a caravan.

As a child, I enjoyed helping out in the house, as most children do. Ma had an old washing machine, not a powered one by any means, but one that had a "posser" on a shaft that was pushed up and down to give the clothes a bashing. The drum of the machine was filled with hot water, brought by bucket and lading can, from the gas boiler in the glass shed, the washing powder and the clothes put in with it, and the posser worked up and down. There was a set of wringers or squeezers as they were known as, fitted to the top of it, which could be let down after washing day to form a flat top, covered by a board. These had rubber rollers, as opposed to the older ones, which were made from wood. Stockley's had one of the old wooden wringers and, when Edna was little, she flattened one of her fingers whilst rolling paper through it! It's no wonder that the women in those days were fit! Anyway, this machine had a bung at the base of the drum for the purpose of emptying it. The original one had been lost for ages, and Dad made another out of wood that Ma had to put in place, and then give a knock with a hammer to tighten it up.

She also used the hammer to loosen the plug to empty the machine. I'd seen this performance many times, and, wanting to help a bit, picked up the hammer, gave the plug a couple of taps, and was knocked flat by the stream of water which gushed from the hole. As luck would have it, the water was only lukewarm, so I just got a soaking. Ma told me that I was lying there; shouting "mamma" as the water came cascading down!!

Those days, everyone seemed to have a "glass shed". In the terrace where we lived, the pantries, or to give them a "posh" name, larders, jutted out from the rest of the house, leaving a gap between. A glass roof and a glass front to form a sort of conservatory, as it would be known as today, bridged this gap, in most cases. Those days, conservatories hadn't been heard of, so it was a glass shed or "shade".

I suppose that it did give a bit more living space, but it was freezing in winter and boiling in summer. The washing machine was installed in here, and I have seen Ma, stripped down to her underskirt, sweating away in the summer heat, at the washing tub, using the rubbing board and soap to get the stains out of the clothing. To try and alleviate this heat, Dad took some corn sacks which he split at the seams, Ma then sewed these together to make a cover for the glass, and it was put into place through the upstairs windows and secured on hooks, screwed into the frame of the glass top. This afforded some shade but it was still quite hot. Washing day held particular memories for me, the smell of damp clothes drying on a maiden in front of an open fire, chips for dinner together with lamb left over from the Sunday roast, with a piece of home made pie for afters. Ma made three or four pies every Saturday, beef, apple, jam pie with windows, custard pie of course, as there were plenty of eggs. The smell of ironing done with a gas iron. It's a something that never leaves you.

As well as the washing machine and tubs, there was a "slop stone" with a cold tap. Slop stone was the right word, as this is where the slops were emptied, it was brown earthenware and about 6ins deep, so washing up or any other task had to be performed in an enamel bowl. This slop stone was in the living room before the shed was built, but had been transferred. Here Dad washed when he came in from the pit. He would strip to the waist, put a towel around him to stop the drips, and then have a wash down in the bowl, which was placed on the stone. Miners those days didn't wash any further down than the waist, and even then, they didn't wash their backs, in case it weakened them. Dad would wash with soap first and then have a swill down with cold water, taking some up his nose to blow all the coal dust down. It fascinated me to watch him as he performed his ablutions.

Later on, we had a large tin bath, which was in the shed next to the pantry. The shed was attached to the pantry wall where it covered the small window. We had a cold-water tap put in, and the gas boiler transferred from the glass shed to there. When we wanted a bath, we got the bathtub from its nail on the wall, and, using a "lading can", put water into the bath from the boiler. A curtain was hung over the shed window for privacy, and the boiler provided heating in the shed as well. This system worked quite well and was used until we moved into the shop in 1945.

I was "assisting" again, when I was in trouble once more. Ma used an old hand brush to sweep the soot from the fire back in the "Yorkshire" range that most households had. This fireplace is worth a mention. It had an oven, and a water tank situated on either side of the fire grate. The water tank was never used for water, but we put kindling wood in it to keep it dry. There was a lift-up lid, which doubled as a hob to stand the kettle on. There was also a hob that could swing across over the flames for the kettle or pan to go on.

By the side of the oven was a draw plate, which, when pulled out, allowed the fire to be drawn under the oven to heat it up. There were three bars across the front of the fire and behind these, the grate and under this was the ash-pit or "ess-ole" as it was known, and a tin was placed there to catch the ash. In front of the ash-pit, a "duster" concealed the opening. This was constructed from a 3-sided piece of metal, and usually had an ornamental design on it. A brass fender surrounded the base of the fireplace, which was covered by an enameled hearth plate, and these plates made belting toboggans when they were bent into a curve at one end!

Anyway, I had seen Ma sweeping the soot down, so I decided to have a go myself. I got the brush and put it into the fire, and, lo and behold, the brush was in flames! I was only about three at the time and Ma told me I went towards her with the brush like a torch, shouting "Look, mamma,"

These Yorkshire ranges were the women's pride and joy. They had brass rails and fittings, which were polished at least once a week, and the rest of the grate was "black-leaded", this being applied with a small brush. I seem to recall that the name of the polish was "Zebrite" and had the face of a zebra on it.

I found this ad in a museum. I recall my Mum using this polish on the grate. After using it Mum's hands were really black and needed a good wash. It was said of one woman though, when asked about the state of her hands, she replied, "It's awreet, Ah'm just gooin' T'kneayd sum bread up, that'll shift it!"

There were no such luxuries as fitted carpets, because, for one thing they would have been too expensive, and there were no vacuum cleaners in those days, only a "Ewbank" sweeper, hand operated, which removed some of the dust. It had a rotary brush in the centre driven by the rubber tyres on the sweeper wheels as they made contact with the centre roller. On either side of the brush were containers for the dust, and depressing a lever on the side of the sweeper emptied these. We had lino on the floor and a carpet square in the middle of it, which was taken outside regularly, hung over the clothes-line, and beaten with a carpet beater made from cane, raising clouds of dust. I loved beating the carpet! In the glass shed was a piece of coco matting, and after kneeling on this whilst playing, you had patterns on your knees.

We rarely had a fire in the front room or "parlour" as it was known, it was only lit at Christmas, or when someone was ill and had to have the bed downstairs. When we did have one, Ma got a good fire going in the kitchen, and, taking a shovelful of burning embers, carried it through the house, with smoke and flames coming from it. I can still smell the smoke that used to hang for ages afterwards! Talking of having the bed downstairs, it was a saying amongst the older people, when someone was really ill, "aye, they've 'ad fer t'get t'bed deawnstairs for 'im"!

I remember what we had in the way of furniture in our house. In the kitchen or "living room", there was a scrubbed white table with varnished legs, re-done at regular intervals with copal varnish. The table had a cloth for everyday use made from a sugar bag, split at the seams, and hemmed by Ma on her old Bradbury sewing machine. It may not seem much today, but we were quite posh, as our neighbours, the Browns had oilcloth and some others had newspapers on theirs. In the Twigg's house, they had oilcloth with squares on it and Irene and Edna used to pretend that they were at the fair and roll pennies into the squares! There were four stand chairs, again varnished regularly, and these had a floral design on the back, cut into the wood. The centre of the flower was like a raised button, and we used this as a bell push when playing "Buses".

The "easy chairs" were anything but easy, as they were made from solid wood and had no springs. The seat and back were in one piece, hinged in the middle, and at the back of the chair was a wooden bar which could be moved to three positions, allowing the chair back to recline. The back and seat were padded and fitted with loose covers. We also had a sideboard where the best crockery and glassware was kept. I think that this had two cupboards and three drawers, one of which was lined with green baize where the cutlery was supposed to be kept. It was made from oak and stood on legs with a space underneath where we could go and play. In the corner near the fireplace and adjacent to the under stairs, was a three drawer chest with a glass fronted cupboard on top. Our Bill, as a little lad, was playing with a toy hammer when the head came off. It went straight through the glass in one of the doors of the cupboard, and Dad had to fix it!

We had a pantry complete with a home made wooden meat safe clad in perforated zinc to keep the food cool and the flies out. The pantry, fitted with shelves on either side, had a tiled floor and here stood a big earthenware bread mug to keep the bread fresh. On the subject of flies, everyone had flypapers hung up during the season to catch them. These were bought rolled up in a tube and they had to be warmed in front of the fire to ease them out of it, before they could be hung. Grandma Foster had a fly swat which I loved using, flattening the flies on the wallpaper!!

Continued...