Parkside Memories, 1959 to 1989

The Spine Tunnels

Wimpey brought in their own foremen and tunnel gangs, and I recall that when the Eimcos arrived at the pit, they had been in Malta and still had Maltese mud on the tracks. The foremen were Tony Divers and Jimmy Frayne, two big Irishmen. I think that Tony came from the Persian Gulf, where he had been on oil installations, and Jimmy had been in Malta. These two were staff men who were retained by Wimpey, and followed the work wherever it took them. Tony told us about the oil drilling platforms in the Gulf, and of how divers would go down to the sea bed to fix the steelwork of the platforms to large blocks of concrete that had been placed there.

Tony lodged in Newton somewhere, as at that time, there were a lot of people who took in lodgers in that area. Jimmy, on the other hand, used to also lodge somewhere local, but every other weekend, he would go home to Hendon, near London. He used to go on the weekend that he was coming off days, driving down after finishing at 7.00 pm. This way he could be home for Saturday and Sunday, travelling back Monday to start work at 7.00pm Monday night. He drove a new Ford Capri, one of the original models.

We had a site agent named Walter Pesch who was a German and the tunnel gangs were usually made up of either Poles or Irishmen. There were 15 in a gang, working three shifts with 5 men in each. In a tunnel, when drilling was taking place, 2 men would drill the top half of the face from the platform and 3 others would drill the bottom half from the floor. Every hole counted and they never took out more ground than necessary. These tunnel gangs were like Gypsies, travelling all over the coalfields, following the best jobs where pay was at a premium.

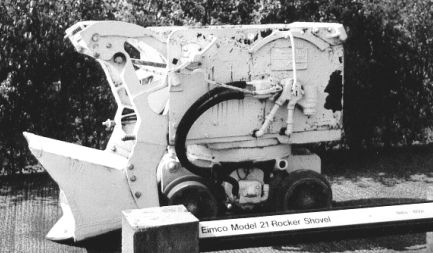

EIMCO 6/20 Shovel as used in No.1 horizon.

Picture taken at Wakefield Museum.

No 1 Horizon was the first to be tunnelled and here we used 30cwt mine cars which had to be coupled in twos to send them up the pit. The pit bank at No1 shaft had, by this time, been constructed, with a tippler to take the spoil and there were two turntables, one at either end of the circuit. The cars gravitated from the shaft, through the tippler, on to the turntable, down to the creeper and up again to the other turntable, from whence they returned to the pit to be sent underground again for re-filling. This was the theory, however in practice it wasn't so simple.

The circuit was supposed to be able to operate completely automatically, but never did. One man was behind the pit, and he gave the clear signal to the banksman, installed in a cabin built over the car track. When the cage came to bank, it triggered the in-line switches by means of a wheel located near the guides. There was a blister on the side of the cage, which pushed the wheel back, and this operated the electro-magnetic switch controlling all the gear relative to the cage on the pit bank. A light showed in the banksman's panel to tell him the cage was in line. He then opened the gates, rammed the empties in, knocking out the full cars. He had to wait for a "clear" signal from behind the pit before lifting to the next deck and repeating the operation. Although the cage had 4 decks, only 2 were used for men and debris for a long time. A similar system operated underground, but here the onsetter's cabin was situated in between the tracks and the system of switchgear was more or less identical.

As I said previously, the "automatic" system was anything but. We had to have a fitter in attendance all the time as the equipment was new and had a lot of teething problems. I recall one incident of note, Joe Lindsey, the fitter, was in attendance when we had problems with the ram. There was a "butterfly" valve playing up and Joe was kneeling in between the track attending to it, when the ram operated automatically, and, even though the air was turned off, there was sufficient left in the pipe to send the ram out. Joe was carried forward by it and nearly ended up in the tippler. It was a lucky escape!

When the shaft was first commissioned for winding, the speed was 44ft /sec for minerals and 30ft/sec for men, but this had to be reduced because, when the main fans were running, due to turbulence caused by air movement in the shaft, one of the cages collided with the counterbalance weight, and a piece of metal was torn from it. The weight by the way was heavier than the cage when fully loaded with men. This was to enable emergency winding to be carried out so that if, at any time, the electricity failed, an emergency generator could produce enough power to lift the solenoid brake on the winder, which always failed to safety and locked the cages in the shaft. Once the brake was operable the cage could return to the surface. If it was necessary to take the cage back underground, two special water cars were loaded into the bottom decks, each filled with water and the cage, now heavier than the counter weight, would freewheel down the shaft, controlled by the winder using the solenoid brake. When the cage was to return to the surface, the water was run off by means of valves in the bottoms of the cars.

No 1 horizon was the only one to be worked with 30cwt cars and 620 Eimcos mounted on wheels. A large pre-fabricated crossing used at the tunnel face was known as a "California" crossing, I don't know why it got this name. This allowed for the shunting of empties and fulls as the Eimcos filled out the heading. The crossing was attached to the 60lb permanent track and from the crossing inbye to the face, double sets of prefabricated track were used. At the end of the week, the prefab track was taken up, the crossing moved forward and permanent track laid. Before charging and firing took place, the track was laid right up to the tunnel face, so that after firing the Eimcos could get right in to shift the spoil. The average "pull" was 7ft and the arches measuring 17x16x12 were set at intervals of 3ft and completely covered in the web with oak lagging boards. To keep the arches secure when firing was taking place, 4 sylvesters and chains were attached, 2 at the shoulder and 2 at the base and these were anchored further back on the set arches and tensioned.

The pattern of firing used was known as a "box burn cut" and drilled as follows:- A king hole in the centre, followed by 4 holes in the shape of a square, about 8ins apart. These holes were then followed by 4 more about 8ins away from them in the same pattern These were numbered 1 and 2 After this the next holes were drilled in twos, 2ft apart and about a foot away from each other. These were numbered 3, 4,and 5, and when fired would pull the middle out. the other holes were drilled in 3s above and below the first series and numbered 6,7 and 8 and finally a row of 5 were drilled at the base and angled down into the floor, these were no. 9s, thus there were 9 half second delays in the firing sequence. Each hole was drilled to a depth of 8ft and when the whole lot was charged, there could be upwards of 40 holes with an average charge per hole of 3.5 lbs of blasting powder. Quite a bang in fact!

The whole face was wired up in a W pattern i.e. starting at one side and joining the wires in sequence up and down again. Each detonator had a red and a yellow wire so no mistakes could be made, as long as a red joined a yellow everything was OK When a round of shots was being fired in the tunnel the regulation distance was 200yds away from the face. We used a resistance tester or "megger" to test the round before firing. This was supposed to be done at the firing point but it was always done at the face as it saved a walk back if a wire had become disconnected.

The loading bucket on the 620 could only load on the flat, as there was no tilt mechanism. There were two Eimcos filling out in the heading, each one hauled a 30cwt car behind it. The method of filling was by means of "up and over". The operator stood on a platform at the side of the machine and he could slew the machine manually about a foot either side. He would drive the machine forward with the bucket down and then raise the full bucket and tip it into the car. These machines were C.A. driven and a man had to handle the hose to avoid it getting snagged. The crossing was so designed that no-one needed to change any points, thus, when the driver had filled a car, he pushed it back, it was unhooked, and sent on to the "full" track, he then picked up an empty and repeated the operation.

The Equipping of No.2 Shaft

As No 1 shaft was up and running as you might say, with the permanent winders having been commissioned, and the decking gear being installed, No 2 shaft was starting to be equipped. This was my shaft, with Pat Scully, Harold Craggs and myself in charge of the job, on three shifts. As the main fans were now installed, all the work had to be carried out in the air lock of No 2 tower, which was over the upcast shaft, and we used the sinking winder for all the equipping.

The first task was to cover the sump hole to avoid any rubbish falling into it. Before any new equipment was installed, all the old concrete pipes, ventilation tubes etc. had to be removed. A platform was constructed from punch plate, fitted with guardrails and a winch, and suspended in the shaft from the capstan ropes that had originally suspended the 3 deck sinking stage. One winding rope was fitted with a cage, which held 6 men, the other rope still having the hoppit slings attached to it. We used the cage to get to the stage and the other side for slinging materials down the shaft. There was a shaftsman attached to each team, and Derek Callinan was with us with Billy Hall and Fred Gee on the other two shifts.

The first shaft job to be done was the fitting of buntons to the shaft side, as these were needed to carry all the cables, pipes etc. These were placed every 75ft, and to fit them, holes had to be cut into the shaft side, using a jigger pick. Actually, boxes had been placed at the right intervals behind the shutter as the shaft lining had been put in during sinking, so it was a matter of locating these and cutting them out. A cross girder was fitted, levelled and wedged into position, and a box made at either end so that concrete could be poured in to set the girder. Two small pieces of girder were fixed from the centre of the beam into the shaft wall as well. When all these buntons were in position, work began on the pipework.

Two 20ins pipes were installed up to No3 horizon. These were to carry the compressed air into the mine, and also to carry the methane that was drained off, up the pit. A time study was carried out to see how long it took to fix the number of pipes in a shift's work, and my gang, under an Irishman named Eddie Boyle, fixed 12 pipes in a shift. This then was the task on which the pay was based. The system of fixing was as follows:- A collar made in the blacksmiths shop encompassed the pipe a foot from one end. This collar had two lugs with holes in them to accommodate the shackles on the winding rope slings and it also had two more lugs set at 90 degrees to the others.

The rider and bell-housing used to keep the hoppit steady on its journey down the shaft, stopped about 60 ft above the stage, held there by two clamps fitted to the guide ropes from which the stage was suspended. Just below these rider stops a rope sheaf was clamped onto the rod and passing over this was the rope from the crab winch on the stage. The rope had two slings attached to its end and when the pipe was slung down the shaft, it was guided into a gap by the side of the stage near the bunton. The slings on the crab winch rope were attached to the other holes in the collar, and these took the weight of the pipe, so that the winder could be signalled away to the surface for another one. Whilst another pipe was being got ready, the first pipe was being installed, thus the continuity of work was carried on.

To install the pipes a gap with a moveable cover had been cut in the equipping stage by the side of the buntons, and into this the pipe was lowered. We fitted the pipes from the top down, and once in position a gasket was fitted and the pipe secured by 20 bolts. Wrist slings were issued as spanners were being lost down the shaft.

The shaft cable that previously had been used on the sinking stage was now used to power a cluster of lights on the platform. This cable was a self-supporting one that could be wound up and down the shaft like a rope, and it was raised and lowered at the same time as the capstan ropes (another name for guide rods). There was a rather bizarre incident that occurred concerning this cable. The stage was being raised to the surface one night, and the man attending to the winch decided to go home and leave it running. No one knew why.

He was an Irishman by the name of Matt Brookes, and it wasn't realized that he had gone, because the cable winch was in a different shed to the main capstan winches, which were operated by the winder himself. It used to take over an hour to raise the platform from No1 inset to the surface and the practice was to leave a loop of cable hanging below the stage. The capstan and the cable winches ran at slightly different speeds, so every so often the capstans were stopped to allow the cable to catch up.

Harold Craggs was the deputy in charge on this occasion. The capstans had been stopped and the cable still running. As the cable caught up again the "stop" signal was given to the cable winch operator, but nothing happened! The cable continued to rise, and as subsequent signals proved fruitless, the cable became tight and began to tilt the platform. The workmen grabbed for the guardrails to avoid being thrown down the shaft. The deputy had the presence of mind to signal the capstans to go again, thus preventing what could have been a major disaster. Needless to say the man responsible was dismissed immediately, but it must have been a "hairy" situation at the time.

Another incident occurred while I was in charge. Most of the gang that I had was Irish, the charge hand being Eddie Boyle, who came from the West coast of Ireland. Just one was a Scot, I have forgotten his name but that doesn't matter. I was up the pit at the time. I wasn't supposed to be, but on the back shifts we kept out of the way as much as possible. The winder, Danny Jones came to look for me. "They've just knocked three threes" he said. This was a signal to say that an accident had occurred in the shaft. I was scared to death!

I went to the pit top and they were just bringing the Scotsman up with a severed little finger. Apparently, he had got it trapped when the clamp on the pipe had slipped. They had just slung a pipe down to the platform, and transferred it to the winch rope when it slipped, trapping his finger, and the slings had been knocked away for another pipe. They then had to wait for the next pipe to be sent down, and this had to be put on the stage before they could take the weight of the pipe trapping the unfortunate man's hand. All this while the man was feeling faint and hanging over the open shaft! He was taken to Warrington hospital where he had his hand "Tidied up" He was back at the pit before the shift finished.

When the piping was being done in the backshifts the gang could fit their quota of pipes, i.e. 12 pipes, in about 3 hours. When this was done they were up the pit a.s.a.p. and playing cards. The game they played was known as "Tonk" and was a similar game to 3-card brag. I got drawn in, but only once, as it cost me 7s 6d,(37.5p) which was quite a lot when wages were only £19 per week. I never played cards for money again after that!!

The pipework proceeded as planned and soon they were all installed. The next job was installing the cables, of which there were 8 altogether. The pipes were in the centre of the bunton, and the cables arranged 4 on either side of them. The largest cable was 4ins in diameter and carried the telephone lines. To support the cables, wooden cleats were clamped to them, one at each bunton and one in between, bolted to the shaft wall, and all the fittings for the cleats were in galvanised steel to counter the effect of the salt in the shaft water.

To start the installation, two pedestals were mounted on the platform and the drum of cable placed in position. The end was anchored at the top of the shaft, in the cable duct and as the stage was lowered the cable was payed out. It's own weight keeping it straight until the first bunton was reached. The first length was the worst one as the cable had to go to No1 inset in one piece, a distance of 300+yds, so you can imagine the size of the drum of telephone cable. It was a monster!

The installation was going quite well, we had installed into No 1 horizon and also into No2. It was the start of the afternoon shift when the incident occurred. I was on the stage with the rest of the gang, and we were attempting to take the cable tail into No3 horizon. To do this, as the cable was too stiff to handle, we had to drop the stage below the level of the inset and push the end into it. To do this we attached the winding rope to the end of the cable by means of a lashing chain. As I have explained earlier, we had the rider on stops 60ft above the platform to facilitate movement of materials. Between the end of the rope and the hoppit slings was an "Ormerod" detaching device that was there in case of overwind. These were pretty common in most collieries. In case of overwind the device was designed to go through a bell housing and by shearing a copper rivet, would detach the winding rope from the cage, the "Ormerod" would open out like a butterfly, and suspend the cage.

As in this case, with the cable being dragged upwards, the "Ormerod " was dragged along the horizon roof with the result that the rivet sheared, and the whole lot came crashing on to the stage. I had to send for the shaftsmen to come down No1 shaft to examine it. I went up the pit myself to see the manager, Bill Holdsworth who was still in his office, and I walked in with some trepidation. "Mr. Holdsworth" I said, "The detaching hook has just come off the rope" He looked stunned! I hastened to say that no one had been hurt. He wanted to know what had happened and I told him that I didn't know, which of course was true at that time. When the shaftsmen examined the shaft wall they found scratch marks and then they knew what had occurred. Any way, after an inspector's visit the whole incident was forgotten.

There were a few incidents that stand out in my memory. In one of these a sinker lost his leg. At the time a camber girder had been lowered down the shaft. It was placed on a bogie so that it could be transported on to the job. Suddenly it rolled over and trapped the man's leg, damaging it so badly that it had to be amputated. The method of transport had to be re-examined after that.

In another instance, we were pouring concrete into the walls at No3 pit bottom. To do this concrete was sent from the surface, ready mixed, down a pipe, from the mixing station. A flexible pipe conducted it from the shaft pipe to a c.a.-powered placer. When this was full, the concrete was blown from the placer to the shutter along a pipe. As the concreting finished, the pipe was washed out from the surface, and the washout run off into a hoppit. The man in charge of the flexible pipe was a Pole by the name of Stefan Stelmachovitz. He wasn't aware of the wash coming down the pipe, the force knocked him off the scaffold, and the wash went all over him. We rushed him up the pit and straight under the shower, but it was too late to save one of his eyes. He was also deaf in one ear as well. The N.C.B. later employed him in the lamproom.

When Parkside was first started, the Nacods (national association of colliery overmen, deputies and shot firers) to whom the officials belonged, met at a pub in Haydock, called "The Wagon and Horses" We didn't have a branch of our own, but were tagged on to the branch from Lyme Colliery. This was OK while there were only a few men at Parkside, and the representatives from the pit who attended the meeting discussed any business. When we started to get more and more officials we felt that we wanted a bigger say in the running of the branch. We put this to the branch, but got nowhere. Sammy Johnson, who was in local politics, decided on a course of action.

We all turned up at the Annual General Meeting. There must have been at least 20 from Parkside, and we outnumbered the rest by quite a lot. Joe McGurk was president and Matt Smith was secretary. We had gone with the intention of getting a delegate on the committee. I recall Sammy standing up and saying to Matt "We could take over this branch if we wanted to" Matt threw his papers into the air and said, "Take it! Take it!" He was really upset!! Sammy said "We only want representation" We finally got what we wanted, and a delegate who I do recall was Tommy Fildes, was appointed to look after the interests of the Parkside men.

About this time, I decided that the old Standard Vanguard was getting past it and I wanted a change. I got a sale for the old car with Chris Farrell, who was a deputy. I think that I sold it for £40.00 or something like that, and I bought a Bedford van, which had been converted into a People Carrier. This cost around £110.00 There were 12 seats in it and I thought that I could make it pay by taking men to work. I'll never forget the first morning that I took the van to work. When I picked it up from Ernie Wilkes, it was dark and when I tried to garage it the garage was too low and the van hit the roof. I had to leave it parked near the house and that night there was a heavy frost.

When I came to start it, I managed to flood the carburetor, flatten the battery, and, as I tried to start it with the starting handle, tore the skin on the palm of my hand! I had to go for our Bill, who came with a spare battery and got it going. All the lads that I was supposed to pick up had gone on the bus and they were all late. Peter Dooley split us up then, so that I couldn't give them a lift, but I got some more clients and managed to keep the petrol money coming in.

Continued...