Park Collieries, 1948 to 1959

The Eastern European Influx of Labour

About 1950 we had an intake of EVWs(European voluntary labourers). These were a mixed bunch of Poles, Latvians, Lithuanians, Ukrainians, and others. Most of these had been displaced from their own countries, firstly through German occupation, and then through Russian. A lot of them had been slave labour under the Nazis, working in factories in Germany, and when the Allies had liberated them, they didn't want to be under Communist rule.

When they first arrived in England they were sent to training camps, Leicestershire and Scotland being just two of them, to learn Basic English, and to be instructed in mining techniques. I recall that first morning when they appeared in the pit yard at Stone's. They were all dressed in old battle fatigues, pit boots and helmets, and they looked a bit lost. They were living in a miners hostel at Haydock. There had been some foreign workers at Stone's when I first started there, mainly Polish ex-soldiers and other service personnel, but these were men who had been fighting in the Free Polish Armed Forces, alongside British troops, and when they had been de-mobbed, didn't fancy a life under Stalin. There were two brothers Jan and Stan Rustyn, who finally emigrated to Canada to work on farms there. Another was Ludwig Novak, who married another Polish lady. We had an old man working with us who always called Ludwig, "Bloodwig"!

There was another Pole who worked on the pit level in No1 pit called Hubert Mindikowski, who had been in the Polish Air Force, and he wore his old Air Force tunic, I don't know where he finished up, but he seemed too cultured to be a pitman. On the whole the EVWs were a likeable bunch and quite hard working, but the native English workforce were against them for quite a while, mainly because they were foreigners.

They weren't allowed to have jobs on the coal-filling shift, those jobs were for "Us", and they were "They". The Poles found themselves put on the ripping and packing jobs, which were usually on the "back" shift i.e. afternoons or nights. There was a lot of jealousy too, when the Poles started to look for girl friends amongst the women in the villages and surrounding areas.

A lot of pitmen had only two things in mind when they drew their pay, Ale and 'orses. They were renowned for the amount they could consume. That and "backing" horses used to account for most of their wages, The Poles, on the other hand, having had nothing to start with, looked after their money, I remember one lad, a Latvian named Albert Klavins, who bought himself a new car, an Austin A50.

It might not seem much these days, but then, most men came to work on foot, by bus or on a bike. I think that there was only the manager at Stone's that had a car at that time, as well as Albert. He told me that he was paying £7 per week for it, when his weekly wage would have been about £16 for 5 days. He worked every weekend that he could to pay for that car!

Some of the Poles had had bad experiences, one of the Ukrainians, Mykola Lytwynenko, told me of a mass grave where the Germans had shot a great number of people and buried them in a hollow, bulldozing the soil on top so that the hollow no longer existed. Zygmunt Misczuk was a slave labourer in Germany. Albert Klavins had been a clerk in the days before the war, and was also a good musician, playing the saxophone. They came from all walks of life, but the majority of them became skilled miners and good workers. Josef Milczarek, one of the intakes from 1950 used to polish his pit boots and press his pit clothes! I don't know how long he kept it up.

There is another tale to be told concerning one of the Poles, a man by the name of Jan Jakobowski. He was only small, and had been in the Free Polish Army. He worked with us on the pit level haulage, and each break time we would congregate in the pit bottom cabin for our "snap".

There was a lad working with us by the name of Martin Quinn, and Martin could roll his eyes back into his head so that only the whites were showing. Whilst doing this, he would hold a copper stemming rod like a spear, and prance around like a dervish and the lads would call this the "black dance." He looked really fierce! One day as little Jan sat there, eating his sandwiches, one of the lads said, "Come on Martin, gi' us t'black dance".

After a lot of persuading and the promise of numerous "chews" he started off. Jan, who had never seen this before, sat there, transfixed! Martin, who could see that Jan was mesmerized, played up to him, and as the dance was coming to an end, jabbed at him with the "spear". I think that Jan must have leapt a foot in the air!!

There were quite a lot of jokers those days. Cliff Green, the undermanager had a table in his office and in the table was a drawer, filled with spanners, which he kept locked, and when anyone needed tools, he would issue them. Unbeknown to him, the night shift deputies, Harry Barrow and Bill Cunliffe, had removed a board from the tabletop, unscrewed the handles on the drawer, and replaced the board. The next morning, Arthur Wadsworth, in all innocence, came into the office to borrow a spanner for a job somewhere. "Lend us a screwkeay Cliff" "Aye, awreet" said Cliff, reaching for the drawer handles.

As the drawer was quite heavy it needed a good tug to open it. Cliff snatched at the handles, which came off in his hands, causing both his elbows to strike the wall behind him!

"Tha knowed us them 'andles wus loase" "Nay ah didn't" "Yah tha did" There was pandemonium in the office!!

Another time, Dickie Atherton, also known as Dickie Appuh (apple, as in apple pie), from the fact that when he was going off shift, and asked how the job had been left, would always say "Appuh pie!" Dickie used to bring his bike pump down pit with him to keep it safe, and would leave it in his Mac pocket in the pit bottom cabin, while he went into the far-end. Harry and Bill knew of this and also of Dickie's habit of taking the pump from his pocket and giving it a couple of quick pumps before going up the pit. One day they filled it with oil and when Dickie went through his routine, oil shot all over the whitewashed wall!!

There is another story concerning Cliff Green. The men used to come out of the far end and they would queue up along the pit level, because at that time the men were wound up the pit in the order that they queued up. Later on it was first down, first up. Well, as with all men, if they get an inch they will take a yard. This day, all the men were queuing when Cliff appeared. They were all out early, and, seeing him, they scattered this way and that. The only one left was a young haulage lad, who stood there petrified. Cliff said to him "It's awreet lad, thee just stop theer." Cliff went into the pit bottom cabin and the men in hiding crept out again and took up their positions where they had been previously. When it was time for the men to ride, Cliff came out and, going to the haulage lad said, "Reet, aw yo men i' front o' this lad, yo're quartered"! He was a crafty old so and so!!

No 2 Pit Bottom Circuit

After my face training was completed, I spent some time working with the men who were re-designing the coal circuit at the pit bottom of No 2 pit. This was to enable the coal from the Yard mine to be off loaded there. Before this, the coal was loaded some 500yds away and then had to be hauled to the pit bottom. In No2 pit you went along the level for 100yds, turned to the right past the old stables, and then up a slight incline for another 500yds, and it was from here that the coal was loaded. The tubs were attached to an endless rope system .The rope itself passed round a "C" wheel three times to give it purchase. The "C" wheel was on a haulage engine built at the colliery and had a strap drive from an electric motor to the clutch and "C" wheel The clutch was cone shaped and clad in copper and was engaged by means of a foot pedal.

When the full tubs started on their journey, only the haulage engine required a small effort before gravity took over and the engineman could de-clutch and the weight of the fulls would bring the empties up. As the full tubs reached the bottom of the incline, the front chain was removed and scotches were put in the tub wheels to bring them to a stop, so that the back chain could be taken off. From here the fulls were unhooked and sent round the curve on to the pit bottom.

The lad on the scotches was Wilf Birkett who used to play football for Southport as a semi-pro, and he could throw the scotches pretty accurately, rarely missing a wheel.

It was decided to abandon this system in favour of the new one i.e.- belt to the pit bottom. To do this, a piece of return roadway running parallel to the pit level was reconstructed, and it also meant the removal of an air-crossing, which was one of the old type, brick built with a timber floor of baulks. The return roadway had to be sterilized by fitting a pair of air-doors 200yds inbye of the air crossing. A short tunnel, driven behind the pit to connect with the old return, was to accommodate the creeper which lifted the empties so that they gravitated along the new roadway to the loading point situated near to where the old air crossing had been.

When the tunnel was complete, the old section of return was re-ripped using 6x5 RSJ, which were bricked into a wall on either side. The re-ripping was carried out on the night shift when the girders were left, supported by props, set about 2ft in from the ends, enabling the wall to be built during the day. Then the following night when the mortar had set, the props were removed, and some more re-ripping done. I was the brickies' labourer for the whole of this job, and it was hard work keeping two brickies going with hand mixed mortar.

The brickies were Syd Williams and Arthur Lowe, Arthur's labourer was a chap named Jimmy Cunliffe and Jimmy was one of the nicest men that you could meet. He was crippled with arthritis, but he always had a smile. When using a spade he had a job to grip it, because his hands were so deformed by the disease. Arthur lived in Downall Green Road, where the motorway runs now, and his house was demolished to allow the road to go through. He stuck out for as much compensation as he could, making the contractors wait!! The wall was 20ins thick and the brickies used a spade to put the mortar on with! They only used a trowel on the final facing bricks, the others were just dropped on to the mortar bed end levelled, so a lot of mortar was needed daily. I went home tired every day!

When the job was completed, the conveyor was extended down from its previous delivery point to the new location. Because Stones's colliery never had a compressed air system, a hydraulic set up was introduced to drive the stop block and rams etc. A manhole on the pit level was converted into a small engine house and the hydraulic unit installed there with pipes carrying the hydraulic fluid to a set of blocks and a loading flap at the loader end, a set of pushing rams on the pit bottom level, and axle catches and rams by the cage. It was a big improvement.

The whole system operated in this way: - Tubs left the cage and were pushed down on to the creeper, which lifted them up to the loading level. From here they gravitated to the loading point, and were filled with coal. They then gravitated to the pit level, where the pusher rams propelled them to the cage and so up the pit.

Whilst working with the bricklayers I was on a job to build a sub station on the pit level of No2 pit. What a job this was! The roof of the sub had to be fireproof so it was lined with old tub bottoms placed over the girders. The worst part was packing behind the walls of the sub with flue dust. This was a very fine ash that came from the fire holes on the surface and it was very invasive, up your nose, in your eyes, it made you sneeze, I remember it well!!

A Collier at Last!

I was given a place on the new Yard Mine face in 1952. It was known as South East one, and had been formed out after the tunnels had been driven through the step in No1 pit. When the tunnels were finally through, a pilot face was worked first. This was done whilst I trained in No2 pit. As the face progressed, a flank face was prepared on the left hand side of the pilot, and it was on this face that I was given a "breyd". It was exciting, getting all my tools together, pick, hammer, spade, wedge, and marking them all with my own name. "FFX". I got the pick sharpener to make me a tool rod to put them on. The 7lb sledge had been my Dad's.

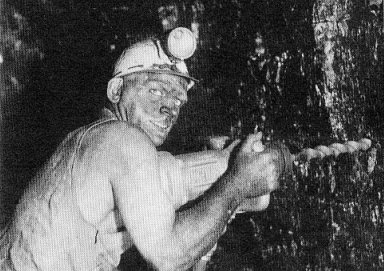

Then came the big day! I went into the yard mine carrying my tools, got down to the face, stripped off to pit drawers and vest, buckled on the knee pads, and crawled to my place, ready for the belts to start up. At that time Fred Kelly was at one side of me and George Travis was at the other. Most of the men on the face had been drawn from the Ravine riseworks, which had finished by then. Bill Tracy, one of the Lyme pits men was "bummer" and Bill Shaw was his second in command.

I wasn't cut out to be a collier, really, but I needed 2years face experience to become a deputy. There was one incident however that sticks in my mind from that first week, I had set all my bars, but the first one wasn't to my liking, so I went back to it. I put my back under it and knocked out the prop, the next thing that I knew was that I was pinned down under a big piece of stone that had fallen from the roof. I had to shout for assistance to some other colliers to extricate me!

The cutterman on this face was a man named John Willie Twist. He liked to be known as John Bill, and he was as bad a cutterman as Arthur Wadsworth was good. He couldn't keep the jib on the floor of the seam, and every two or three days we had to stop production and get the bottom coal from the floor to get some working height.

At this time our wage for the week was low, around £10, as it was based on the tonnage filled. The final straw was when John Willie managed to cut so badly that the shot holes drilled near the top of the seam were cut out at the back of the cut, he was so far from the floor!

Uncle John said "That's enough" and John Bill was demoted to afternoon shift, turning the cutter round. Arthur Wadsworth was brought in and our wages went up to £16 a week.

Working on this face at the time were Wilf Phillips and Fred King who trained with me on the No2 face. Fred had been off work with a mystery illness that I never knew the name of, but he had been quite ill. One day in 1952 when we were getting ready to go on to the face, one of the men said "Hast heered t'news? King's deeud." I was shocked! "I didn't think that Fred was so bad," I said, "Now" he said "It's King in t'Buckingham palace wot's deeud" I felt daft but relieved!

Another man that worked on that face was Tommy Heaton from Upholland, Tommy's habit was that every morning when he was stripping down to drawers and vest, he would relieve himself on the main belt and watch the stream of urine as it ran down to a joint and disappeared.

Tommy had two brothers who worked at Stone's, Ray and Kenny, and if Tommy overslept, so did the rest! He had to go and knock them up, Ray had two alarm clocks in a bucket, but never heard them, and Kenny had rigged up a system of paper clips made into a chain, fastened to the alarm clock key and then to a switch of a battery operated electric bell. This would waken him, but Kenny would leap out of bed, switch off the bell, and jump back in again, thus defeating the whole object of the exercise!

When the face on the left flank had reached its boundary, we transferred to a face on the other side, this was known as SW 1, and there were others that followed SW2, 3,etc. Each face unit was 250 yds long split in the middle by the main gate road. The face advance at that time was around 8 yds a week.

As soon as SW1 face was ready for working, it was fitted with "bottom belt loading" This meant that the coal was thrown on to the bottom belt instead of the top. There was no structure on the face for the belt to run on, instead, the top belt was returned along pieces of 2in pipe, which were placed along the face at intervals of about 8yds.

The pipes were pushed into the pack at one end and tied up at the other by a piece of bell wire. In the main gate, the belt drive motors were placed at the opposite sides of the belt, and a plough was fitted to sweep the coal on to the main belt. This meant that the motors had to run in reverse. It was a lot better for the belt shifters in the afternoon shift, because they no longer had to maneuver the heavy trays through the gaps in the props, all they had to do was break the belts on the joints and, having rolled them up, push them through the gaps and re-assemble them.

Another idea was brought in later. Instead of the belt motors having to run in reverse, a pulley was fitted to a dowty prop, and this was set about 2yds under the face edge at the main gate, at the side of the belt. The bottom belt, full of coal, ran over the drive head, delivered, and then returned on the twist, along the vertical pulley, and then continued as the return belt along the pipes. This idea worked quite well, but at that time, a fitter by the name of Frank Jackson, claimed that it was his idea and that the management had stolen it from him. I don't know how true this was but it rankled Frank for years later.

When I started on this face, I was placed at the return end, working with a man named Jimmy Kellely, a man given to chewing tobacco and having a very wet mouth, which meant that you had to watch where you put your hands, as there was tobacco juice spat everywhere! Jimmy never married, and he liked his ale, so it's probably as well that he didn't marry or there would have been problems. When he arrived for work in the morning he was usually "hung over" from the night before, and smelled like a vault!

We always seemed to be late getting our coal filled off, and it was after 4.00pm many a day when we got up pit. There were no pithead baths those days and we went home dirty. I sometimes got home, had my dinner, and then collapsed on the settee, still in the "black" until after 7.00pm. We only used to wash from the waist upwards in those days; I don't know why, because we had a bathroom at home, I suppose it was a tradition. My mother used to put old army blankets on the bed so that the dirt wouldn't show! I recall going to a wedding reception once and seeing one of the colliers there from the pit, and, as he was sitting there, having a pint, his trousers rode up to reveal yellow socks and black legs!

Drilling for a Living

I stayed as a collier for a year or so, my weight at that time was around 10stone and I looked pretty thin. I gave up on the "weed" about this time, packing in both cigarettes and chewing tobacco. I also felt that the rest of my face training could be achieved with a lot less effort, so I asked for a change. I got the job of drilling shot holes on the face, a job that started at 9.00am; it was a really easy number. There were 4 of us, 2 to each side. Peter Byrom from Poolstock and me on one side, Cliff Houghton and Albert Partington on the other.

We would arrive at the pit at about 8.30am, having bought some morning papers on the way, go to the fitting shop and pick up the drill bits that we had left the previous day to be sharpened, and go down and laze about for a couple of hours until the face was nearly clear of coal, and then, when the colliers were down to their last shots, make our way on to the face, coil the cables up and make a start.

The holes were drilled just under the dirt band with a 4ft drill and spaced out at 6ft intervals. The drill bits were held in place with a split pin, and we used to use old detonator tins to keep the spares in. As well as drilling the face, we drilled the roadways as well, and if everything went according to plan, we would be finished by 3.30pm and would make our way slowly towards the pit to get up for 3.45pm. My weight shot up by a stone and a half!

Later on Peter Byrom and Cliff Houghton moved on to ripping jobs on the face, and new faces came on to the job. One of these was Arthur Chivers, whose son was the Lansdale manager at Parkside in later years. Arthur was losing his hair, and he had a saying, "I don't care about t'thatch as long as t'stack sticks" One day, as we were going towards the face, we came across a switch attendant, Gilbert Greenall, asleep at his post. Arthur crept up to him and shouted in his ear. Gilbert shot a foot in the air, and the air was "blue". We had some fun those days.

About this time, the baths were opened at Stone's. Until then, everyone went home in the "black". There is an amusing tale to be told about the baths. We had a fireman in No 2 pit by the name of Handel Turton (I think that his father had a thing about music!). George Ashurst, one of the management trainees, said to me, "hast ever seen 'andel beawt 'is 'at" I couldn't think that I had. George said, "Watch 'im when 'e goes into t'pit bottom office at th'end o t'shift". I paid special attention one day, and sure enough, Handel went to the back wall of the office and, cap in one hand and holding on to his helmet with the other, he did the fastest changeover that you could imagine. He was bald and was ashamed of the fact!

Those days the firemen used to change their helmets for caps at the pit bottom and some of the men used to lock their hats on the tool rod at the face. I don't suppose that it occurred to them that they could hurt their heads on the way out. When the baths opened Handel just walked in, stripped off and had a wash, he never gave his bald head another thought!

Those days a lot of men wore clogs, but with the advent of the baths, boots became more prevalent, because the heat of the lockers dried out the wooden soles and the welting nails sprung out, causing the clogs to disintegrate. I think that the ones who carried on wearing them used to go home in them to avoid leaving them in the lockers.

Shotfiring Training at Ravenhead Colliery

At last the day arrived when I turned 23 yrs of age, the legal age for shotfiring. I was enrolled in the course at St Helens technical college, along with Frank Bourhill, who had been a collier in the Ravine, and Albert Johnson who had been a shotfirer, but, as all deputies needed the new style certificate, he was sent along with us to get it. The place we were sent for practical training was at Haresfinch, St Helens. It was across the road from the float glass works of Pilkington's. Of course it's long gone now, but then, there was a surface gallery mock up to practice making up and stemming shots, a classroom, and a canteen.

Our instructors were a Mr. Blinstone who had been in management somewhere, and a Mr. Smith, whose brothers worked at Stone's, Jimmy, who was on the haulage with me, and Wilf who was a collier on the Yard mine in No 2 pit. Mr. Blinstone took us for mining practice, ventilation, and general pit work, and Mr. Smith for mechanical engineering, i.e. pumps and haulage engines. Mr. Smith would take us in the afternoon, when concentration was at its lowest. He had a droning voice, which lulled you to sleep, and as you looked around the class, you could see the men closing their eyes and drifting. Just as sleep was taking hold, he would start to draw on the board, and this would waken everyone up again, as we all endeavoured to draw as good as he could. He was a belting drawer.

We used to spend one day a week at the training gallery and the rest was spent at a colliery. Albert and I were based at Ravenhead, otherwise known as "Grove's" and Frank was at Wood pit. We had 6 weeks intensive training to do for our certificates.

At Ravenhead, I was placed with the deputy on the shift, and we had to cover all three shifts to be able to watch all operations, and each day we had to fill in a mock report, which was countersigned by the manager, just like the deputy's report.

At Ravenhead the baths were rather old, and had been built about 1930. The lockers were fastened by means of a personal lock, which each man had to supply himself. One night I was coming on shift and hadn't seen the notice about swilling out of lockers. When I opened my locker, my pit clothes were wet through! I should have moved them over the morning previously, and not having seen the notice I missed off. The baths attendants couldn't take the locks off so they just carried on swilling! I didn't do it again, and as it was, I had to work all night in wet clothes.

Coal filling at Ravenhead was carried out on all three shifts, depending which mine it was. I was in the No11 pit for most of my training, and the seams there were Trencherbone or T-bone, and Main Delph. The T-bone was about 4ft thick and the Main Delph about 5ft6ins.

I spent a lot of my time on the T-bone with deputies, Tommy Plant and Bert Helsby. Tommy was on regular nights and Bert on regular afternoons. Both the Main Delph and T-bone were coaling on weeks about, i.e. days and afternoons. The roof on the T-bone was very hard; in fact, it wouldn't break down in the waste. As a result, the coal was pre-fired on the previous shift. It was cut using a cutter with an overhead jib at about 3ft from the floor.

The driller, who used a compressed air machine known as a "flying flea" would put holes in the bottom at an angle, drilling down from about 2ft into the floor, he then would plug these holes with a stick so that the shotfirers could locate them. The driller was paid 6d per hole drilled and 1d for each hole marked.

The shotfirers worked in pairs, they each carried 40 detonators, and they would fire all of one man's first and then start on the next. This is how it worked; they would stem up two shots, couple up to the first and tie the wires of the second to the cable. They then moved about 10yds away, and fired the first shot, when they returned they could locate the next as it was tied to the cable. Before they fired this one, they would stem up the next and tie that to the cable, and so on, until all the shots had been fired. One shotfirer would be coupling up and the other firing when he was told that it was ready.

This once led to a rather nasty accident. Most of the time, there was no stemming available, so coal was used to stem the holes. When the accident occurred, Harold Cunliffe, a colleague of mine at Stone's had transferred to Garswood Hall, and was working with another shotfirer, doing the same job as the ones at Ravenhead. Harold had coupled up and the other shotfirer thought that he had shouted "right," so he turned the key on the exploder. Harold was stood in front of the shot hole, took the full force of the blast, and was peppered with small coal. He carried the scars to his dying day.

They fired the bottom shots first so that the top ones wouldn't cover them up. They could probably get the whole face fired off in about half a shift and then spend the rest of the time in the gate-road asleep.

This idea of firing all the detonators off was prevalent in a lot of pits. In some cases the shotfirer wasn't allowed up the pit until he had fired all of his dets, and this of course led to a lot of malpractice, such as getting rid of detonators by sticking them into the pack and firing them off. A nasty accident once occurred at Garswood Hall colliery, due to the practice of firing dets off. A shotfirer was dropping the dets behind a corrugated sheet, used as a piece of covering between two arches, and coupling them to his exploder, was cracking them off. Another shotfirer, unbeknown to him, had hidden some blasting powder behind the same sheet. Unfortunately, the dets came into contact with the powder and the resulting explosion killed the man.

The conveyor on the T-bone was a Victor scraper chain. This had a chain with flight bars spaced at intervals of 18ins, running in the centre of a pan, and it had to be graded so that the chain wouldn't ride out. If it did ride out it could cut through wooden props like a saw. These conveyors were vicious things, we had one on a face at Stone's and a prop got fast one day. As it freed itself, it shot out like an arrow from a bowstring, and damaged a man's arm so badly that he never worked again. They were finally scrapped when the AFC was installed in all the pits.

The props used on the T-bone were made from small section RSJ with the ends closed off, and W bars were used in the roof. Every day, after the cutter had been through the face, the roof converged about 6ins. It broke off at the face edge and came down, and this was really scary until you realized that it wouldn't come any further. It drove the props into the floor of the mine. Putting packs on in this mine was a bit of a farce, as the waste never produced any loose dirt. In fact, the packs were dirt stacks, made by using chock pieces, domino fashion, criss-crossed up to the roof, and filled with whatever dirt could be found. You could see into the waste for some 30 yards to where the floor and roof met. The stacks built the previous day were cannibalized to provide material for the next days work.

It was quite warm in the mines at Ravenhead. As we left the pit bottom, we entered the return roadway to ride into the district. I had never seen a manriding train before. It was a set of custom made carriages, each holding about 10 men. I think that the train would hold 40 men on each ride. The rail system was fascinating, as it had 3rails down to the crossover point where it became 4 rails. At this point the two trains passed each other. The carriages weren't closed in, and as you went along, you watched the men in front to see when to duck down, to avoid collision with the roof, where crush had taken place. There were about 4 places where this occurred and it was being repaired.

Each train had an arresting device at the front, a piece of RSJ drawn to a point and held up by a pin which could be pulled in case of a runaway, this, in theory, would stop the train but I don't recall seeing it used at any time. Signalling was by the 3-wire system, powered by Leclanché cells, as was the signalling used at the time all over the coalfield. A piece of hacksaw blade was usually used to make the contact. The first rider went for a distance of 500yds at a gradient of 1in6 and then it was a walk of 200yds along a level tunnel cut through the rock, without any supports. Here were situated 2 "torpedo" fans, which boosted the air supply. From the top of this tunnel was another rider of 500yds in length and a gradient of 1in6. At the end of this rider it was only a short walk to the face of the T bone seam. To get to the Main Delph seam you left the second rider about 100yds back from the terminus.

I went into the Main Delph seam one night to watch the shotfirers at work. As they fired the shots, the coal would "burst off" with a bump and a crunch, frightening anyone who wasn't used to it. When all the coal had been fired, there seemed to be a sea of coal ready to be filled off the following shift, and the conveyor belt on this face was 26" wide as opposed to 20" elsewhere.

Continued...