Park Collieries, 1948 to 1959

Training for Underground

The day finally arrived that I had been waiting for, to start underground training. In the Wigan area, training was done at Low Hall training centre at Lower Ince, and at Wigan Junction colliery training gallery. I was sent there on the Monday morning, and when I arrived, the other young hopefuls joined me. I suppose there would have been about 10 of us in the group and we were under the supervision of an ex-deputy, Bill Picken, who came from Pemberton somewhere. We met at the training centre suitably dressed in pit clothes, complete with helmets, which were a novelty in themselves, as we had never worn them before. To get there, you took the bus to the "King Billy" pub, and then walked down the road a bit before you came to Low Hall. We always went into the canteen before going underground; I suspect that this was as much for Bill's benefit as it was for us. We had bacon and chips every morning! Our canteen at Stone's only served pies and sandwiches, so this was something of a novelty. Leaving here, we picked up our lamps and made our way to the shaft. We used the upcast shaft to go to the gallery, as the main shaft was winding coal. There was a single cage in the upcast, as was common in a lot of pits, the upcast being used mainly as an emergency exit and for ventilation. The wind was slower due to the cage being unbalanced, and the cage, which was quite small, held 10 men, standing upright. As we entered through the air lock, the smell of the pit was there, stale air, powder smoke, oil. All the essence of the mine, we thought it was wonderful!

We went to a "mouthing" some 60ft from the bottom of the shaft, and we could see the lights there visible through holes in the cage bottom. As the cage stopped, Bill, acting as onsetter, reached out and pulled a platform or "leaf" as it was called across the gap so that we could get out. From here, we walked "Indian file" to the gallery. This consisted of 2 roadways and a small coalface, which was about 30yds long and 5ft in height.

In the intake roadway was a compressed air haulage engine, connected to an endless rope system. It was only there to show the trainees how to "lash on" using chains and also how to use the Smallman clip for under-rope haulage. Bill gave us instructions, "Gerrold o t'chain, wi' one 'and un' 'old th'ook in t'other. Gi' th'hook a perk o'er t'rope un' slide it back alung it, gi' it three twists an' then put t'chain i' yer other 'and through t'hook an' that's aw there is to it" It seemed so simple! Some never got it right. I never saw a Smallman clip in use in all the time I spent underground at Stone's.

One section of the roadway was in need of repair, as there had been some breaking up of the strata over the top of the girders supporting the roof. It was given to us, under supervision of course, to put it right. The girders were only light stuff, about 3x3 ins RSJ, and we really thought that we were pitmen good and proper, doing this job. There was about 12ins of rock that had pulled away from a natural parting, leaving a good, sound roof to work to. We had to re-set the girders to this new roof and pack the surplus rock on the side of the roadway, between the props.

One day, Bill said that he would take us on a visit to the working face, and show us the coal cutter at work. We all trooped off with him to this face, which was about as high as the Orrell Yard at Stone's, 2ft 9ins. We gathered on the face and waited for the machine to go past. It was an AB 15 cutter, with an undercut jib, and as it cut past us, the weight came down on to the props, which started to creak and crack, a perfectly normal process, but we didn't know it. We all made a dash for the roadway, much to the merriment of the cuttermen!

The period of training was just 2 weeks, and in this time we spent a day at Bamfurlong Mains colliery stacking props. We also had a bit of classroom instruction at Low Hall. One of our number was a fair artist, and one day he was drawing a sketch on the board with a piece of chalk, the only problem was that it was steelworker's chalk, and when the instructor tried to write on the board afterwards, his chalk just skidded off. That raised a laugh! I never met or saw any of the lads afterwards that were with me on the course. It's funny, that, you can be with someone for a fortnight, and then never see them again. I came away from Wigan Junction with all kinds of ideas of what it would be like down pit, but returning to Stone's, they all went out of the window.

Starting Work Underground

I started back at Stone's on the Monday morning, and I was assigned to No1 pit. I was a smoker then, so I left my cigarettes with one of the girls on the brow. No1 pit was about 187yds deep, as opposed to No 2, which was 360yds; this was due to a fault line that ran in between the two shafts, known as the Bull stake fault. No3 shaft connected the two and this was the upcast. There was a Walker "Indestructible" fan installed in a drift, connected to the top of No3 shaft, and down this shaft also ran the ropes from the steam hauler, which ran the haulage system in No 2 pit. Originally this hauler had also powered No1 pit haulage but this was no longer used.

I joined the rest of the pit bottom lads on the brow, having drawn my lamp from the lamp room. We were the last to go down, just after the 6.50am whistle had sounded. We started sending coal as soon after 7.00am as possible, and my first job underground was "hooking up". I had to stand in the last tub, and as the other two lads behind the pit spun the empties round on the landing plates, they pushed them on to the "horseshoe" to put them on to the track on the left side of the pit. I then reached down and coupled them up to the rest, clambering from one to the other to do so. On this job your hands were soon covered in dirt and grease. I must have been fit, as during the day, at least 1000 tubs were sent down the pit. This spinning of the tubs on the landing plates was known as "riving", but for a long time I thought it was "writhing"!

One of the other lads by the name of Freddie King came over to me, "Dust want a chew?" He said. I'd never tried to chew tobacco before, but being a "pitman" I decided to give it a go. It burned my throat, and really tasted foul but I persevered, gallantly chewing away and spitting the juice out! I really don't know how I managed it. The trick was never to swallow the juice. Fred kept me supplied all week with "chews." I think that it was called "Tony Brown" and was sold in shilling (5p) screws, i.e. just less than a half ounce wrapped in wax paper. At the end of the week Fred said "It's tha turn fer t'fotch nex' wik", so I had to supply the tobacco!

The onsetter and his mate, Fred Pye and Jack Parkinson, were the men who put the tubs in the cage. The tubs were held back by a catch in between the rails and this was released by depressing a foot pedal, which allowed 2 tubs to come through. The onsetter could usually gauge this operation to perfection, so that, as the bottom of the cage came into view, he would release the tubs, which just reached the cage as it decked, ramming the empties out.

The operation would then be repeated on the second deck. Each deck of the cage was fitted with a set of control gear, and as the tubs ran in, the axles turned a toothed wheel, set in the centre of the cage floor, and this, in turn operated the catches to hold the tubs in the cage. As the cage decked, there was a set of catches operated by means of a lever at the back of the pit and these were worked by the lad there, who had a bucket filled with sand, to use on the catches when they were wet and slippery, due to the water that constantly dripped down the shaft. The top deck was always emptied first, and then the cage lifted to empty the second one. It was a slick operation, provided that the winder didn't come in too slow, because then, the men couldn't hold back the tubs, and two tubs were in the "dib-hole", or sump. These then had to be dragged out by a chain, attached to the cage bottom and the coal filled out by hand. Fortunately this didn't happen very often!

The signalling system at that time was pretty primitive. It consisted of a line running up the shaft to a "clap-knocker" (like a hammer on a cranked shaft, hitting a metal plate). The line was attached at the shaft bottom to a chain, which the onsetter pulled to give the signal.

Fred Pye didn't like to wear a pit helmet, and always wore a flat cap. As the pit level was well lit he didn't need to wear his lamp. There were very few boots worn those days, as most men wore clogs. When I first started underground, the pit level was a bit on the low side; in fact the tubs were only just going under the girders without touching. The level was being re-ripped during the night shift, where two men were engaged in removing the bent girders and replacing them.

On one side of the level ran the delivery pipe for the pumping system. This was a range of 10ins cast iron pipes, delivering water to the sump hole in the pump house behind the pit. Most of the water came from the Ravine seam, and in the pump house were two Mather and Platt centrifugal pumps, which I had watched Fred Pye and Syd Kear, start up. First of all, the by-pass valve was opened to allow water into the pumps. Then the "pet taps" were opened to blow out any trapped air. The smell of the water as it came out of the taps was just like "rotten eggs". This was due to the hydrogen sulphide in the water, which occurs when acid water is drawn over iron pyrites in the strata.

Syd was known as a "pusher on", and he seemed to be a man who could do almost anything. He wore a pair of riding breeches and knee length stockings. I suppose that his real job was to make sure that the haulage system ran smoothly. When all the air had been cleared from the pump, the bypass was closed and the pump started up. The main valve was then opened slowly, and an eye kept on the ammeter. You could always tell that the pump had picked up when the clock showed 30amps. The water came into the lodge hole via a box, which had a "V" notch for the water to flow over. By measuring the depth of the water flowing over the "V", it was possible to calculate the flow in gallons per hour. I used to know the formula but it's a long time ago!

When the empties were coupled up to the rest of the tubs, or "set" as it was known, along the pit level, a shout of "tail up" was given. There was a lad at the front of the set with a haulage chain attached to the leading tub, and he would put a half hitch on the moving haulage rope to pull the set forward.

On this side road was about 15yds of a flat and then, the roadway started to rise to the same level as the full roadway. About halfway up this rise was an axle catch, which stopped the empties from running back, and as more empties were added to the set, the lad with the chain would have to put a couple of hitches on the rope to haul the empties up. By the time the set had reached the Orrell Yard entrance, there would be about 50 empties in all. Here, he would knock off the chain and go back to the pit bottom to start again.

Situated about 50yds inside the Yard mine entrance was the delivery end of the conveyor belt, bringing coal from 2 faces. About half way up the empty road along the pit bottom were the tub axle greasers. These had to be filled with smelly black grease, and it wasn't a job that was particularly pleasant! However, a lad called Ronnie Phillips would do anything for a "chew", so we would bribe him to take our turn in filling them!

Whilst working on the pit level, I managed to pick up a couple of permanent scars. One day I was lifting the haulage rope on to the top of the empty tubs when a broken strand went into the side of my hand. As Fred Pye was seeing to it for me, I fainted, something that I had never done in my life before. I felt so foolish when I came round. I remember hearing Fred shout "He's gone, Jack" Another time, when we were trying to re-rail a tub, I trapped my little finger and pulled the nail out at its root, and the nail still grows crooked! Again, another time, I was working on the pit level when I got my arm caught between two tubs, and lost a piece of skin near the bicep, and the scar is still there.

The haulage rope ran from the pit bottom, along the level, and into the Ravine Lower Side. It fed the Yard mine, Ravine Riseworks and Ravine Lower Side. Just a word or two about the layout of the seams that were being worked at the time. The Yard mine and the Ravine or Plodder as it was also known, were about 50yds apart horizontally, with the Ravine seam being the uppermost, and there was also a fault of about 50yds as well. The entrance to the Yard mine was the first along the pit level, about 50yds to the left-hand side. Another 20yds and the Ravine riseworks entrance went off to the left also.

Ten yds further along the level were the old stables, where years previously, the ponies had been kept. Twenty yards further, and the roadway made a 90-degree turn to the right into the Ravine lower side tunnel. The haulage engine that drove the rope was in an engine house halfway down this tunnel. At the Yard mine entrance, the rope ran over a "star" pulley, so that the full tubs could run underneath it.

The undermanager at that time was a man named Ben Melling from Haydock, and Ben had an idea to make the "tailing" up from the pit bottom a bit easier. He had the blacksmiths make him a haulage chain with a "knock-off" shackle attached to one end. The idea was that the lad in charge of the set would attach the shackle to the leading tub and then lash the chain to the rope, and as the empties were drawn along the level he could stop them by knocking the shackle off and then remove the lash. This way it would avoid having to use a double hitch.

We tried the idea out one day, and all went well until the set reached the Yard Mine entrance. Here the weight of empties was too great for the shackle to be knocked off, and the chain ran over the star pulley. This pulley was so designed that the chain would by-pass it, even when attached to the rope, but on this occasion it didn't and the leading tub smashed into the pulley, stalling the rope. When we finally got it free, Ben, thoroughly disgruntled with the idea by this time said "clod it in t'pack" Exit another bright idea!

I progressed from the pit bottom job to the Yard Mine loader end, and here I was part of a team of lads whose job was to keep the loading point supplied with empties. The loader was Jimmy Littler and his mate was Tommy Lee. Tommy never wore his false teeth at work, but only put them in when doing his "other job" as doorman at the Scala picture house in Ashton. Jimmy was a short, stocky man with a shock of unruly black hair.

When the set of empties appeared at the entrance, one of the lads dragged the rope down to haul them inbye. The haulage engine was in a recess by the side of the roadway inbye of the loading point, and could be used to haul empties in and also lower tubs down the tunnel that went into the seam itself. The rope had to be taken round a return pulley when hauling up from the pit level, and occasionally it came off this and ran on the axle with the result that it was stretched and became like a spiral spring!

The end of the rope had a sort of a spiral shackle known as a "pig tail", this was attached to the empties and they were hauled into the level. There was a re-railer or "chucker-on" about 5yds inbye of the entrance to re rail the tubs, because, as when they came round the corner, they all came off the rails. There was a set of points behind the loader, which were spring loaded, and as 8 empties passed over them, the tubs were unhooked and run under the loader arm.

When the coal was coming off at full speed, usually just after the 10.00am break, we could fill 8 tubs a minute. Jimmy used to wear a padded mitt on his right hand, which he used to level the load out in the tubs, and, to control them as they ran under the belt head, he had a "blocker", made from a piece of 2x2, about 18ins long, and ironclad which was fastened down with a bolt through its centre. This, he kicked under the tub wheels as they ran towards him. He looked like he was dancing when the coal was in full flow, as he kicked the blocker in and out again!!

He was paid a shilling (5p) by each collier on the face, and with 2 faces producing, about £2.50 was added to his wage each week. This was about as much as we, who were working with him, were getting for a week's wage. It's no wonder that he used to push us on!

I recall that when we got our cans filled up with hot tea at break time, to keep them warm, we used an oil lamp with the flame turned up and placed behind a metal shield, which was nailed to the wall. It was all strictly illegal but it worked a treat! Every morning the lads would give their orders for hot pies and sandwiches and tea, if they wanted them, to the girls on the pit bank. These would be obtained from the canteen, put in a tub just before breakfast time, and sent down the pit. I found out that the charge for a can of tea was the same (6d) for any size of can, and I had a 4pint can! We used to share it out between about four of us, until the canteen staff rumbled the dodge and started to send it down half-full!

At Stone's it was always known as "breakfast" on the day shift, "teatime" on the afternoons and "supper" on the nights. The word "snap" only came in later on. Sometimes break time was known as "jackbit" One lad, Ronnie Roby, the same one who used to tip on the surface, he with the size 14s boots, had a prodigious appetite. He could see off 15 rounds of bread and butter and a meat pie! His appetite for ale was as big, but even after a session, he never appeared to be drunk. His dad, old Fred, who was a packer on the afternoon shift, said that the ale was flat by the time that it had reached Ronnie's stomach. Ronnie was a big, gangling lad at that time.

We had another lad working with us, Dick Cunliffe, who worked at the top of the Ravine tunnel, lashing on. Dick was always playing with a knife. He would come up to you and, taking hold of a button on your coat would say, "Do you want this?" If you said "No" he would cut it off and keep it, and if you said "Yes", he would cut it off and give it to you, you couldn't win and it was no use arguing, as he was bigger and older than most of us.

One advantage of being at the pit bottom was that we came down pit last and got up first. I graduated from the Yardmine job to the Ravine Riseworks, the job was OK but I had to start doing afternoon shifts. I hated them!! I was going out with Edna by this time, and afternoons meant that I didn't see as much of her as I would have liked.

There was a haulage engine at the bottom of the incline, and a manhole by the side of it where you could go to keep out of the draught. The main problem was keeping your eyes open! The empties were sent up in sets of 6, and the fulls came down the same way. The engine itself was made by a firm named Woods and it had a wind on clutch wheel. This tightened a pair of Ferodo lined calipers on to a revolving drum. The brake handle was a cantilever, which could be pinned down. These days it would have been condemned out of hand. The end of the rope was fitted with a "knock-off" shackle, held together by a pin, which could be taken out when the set of tubs had reached its destination, and signalling was done by use of a clap knocker.

The man in charge of the shunt at the top of the brow was a real character by the name of Jimmy Smith. There was no phone for communicating with, and any message was written on the tub in chalk. When I was in need of a "chew", and without supplies, I would write on the leading empty "Send us a chew" Jimmy would oblige, and fastened to the drawbar of the full tub would be a piece of cap wire with the chew secured at the end and an arrow pointing to it.

I recall getting an earful one day from Pee Heyes, who was the fireman in charge of the district. I had the habit of, once the tubs had started to run down the incline, lifting the brake and letting them come down fast. The railroad was a good one and if they came down fast, they would carry on right to the pit level, saving me a job of pushing them out. This particular day, Pee was coming down the brow when I let the tubs run. He thought it was a runaway!! He dived into a manhole at the side of the track, and was scared out of his wits. He didn't half do some shouting and swearing when he finally came down to me!

There was another incident, which occurred very much in the same manner, but this time it happened to me. I was sat in the manhole, waiting for Jimmy Smith to knock for me to lower the full set, when I heard this roaring noise. I was petrified!! I tried to get further into the manhole, because I had guessed that it was a runaway. Two full tubs came careering down the incline and smashed into the warrick girder at the bottom, followed by Jimmy, coming down as fast as he could. He explained that he had forgotten to hook them up to the rest of the set, and when he had knocked out the stop blocks, the first two tubs had set off on their own, and he was powerless to do anything about it. It certainly scared me!!

The lad on the opposite shift to me was Jimmy Simpkin from Garswood, and his sister Olive worked on the screens. I'd taken her out one night, but wasn't really keen on her. She was one of those that Uncle John had warned me about!! We drew a lot of our labour force from Garswood, Downall Green and Billinge.

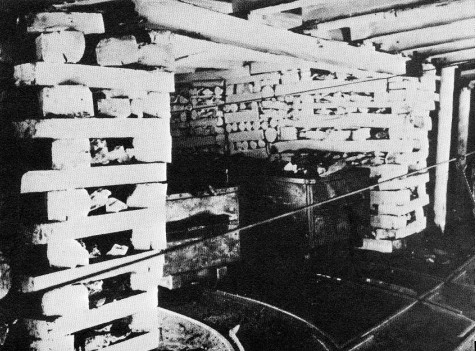

All the coal from the Ravine seam was worked Pillar and Stall, and was all hand-filled into tubs by collier and drawer, working together. Another name for this method of working was Strait work, or Bord and Pillar. It involved driving 10ft roadways through the solid coal for a distance of 25yds and then forming a square junction. From here, another roadway was driven at an angle of 90degrees for another 25yds. This was then repeated until a square pillar of coal was left.

As each pillar was completed, another roadway would be driven to form another pillar and so on, until the boundary of the take had been reached. Then the pillars were split into four pieces by driving roads through them, and when this had been done, the next step was to "rib off" the small pieces that were left. i.e. take slices off the pillar until it had all been removed. To achieve this safely, a row of hardwood chocks or "stacks" as they were known, was erected on the waste edge of the roadway. As each successive slice was removed, another row of stacks was built. The roof in the waste was allowed to fall.

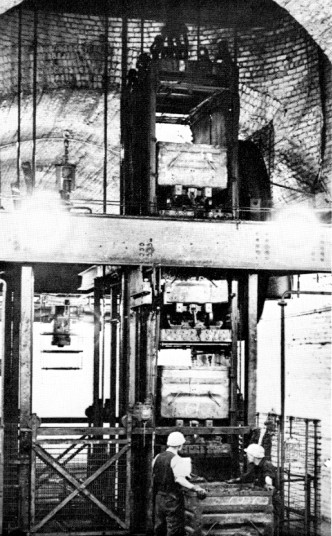

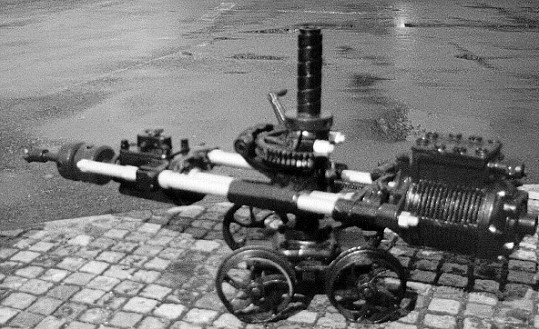

To cut the coal, a fearsome looking machine known as a Siskol was used. It was mounted on iron wheels to run on the track and it had to be manhandled into the working place by the men concerned, and when in position, a couple of chock pieces were placed underneath it to lift it from the rails. On top of the machine was a screw jack, which secured it to the roof, a chock piece being placed on top of the jack for maximum adhesion.

In the centre of the contraption was the working part and this consisted of an electric motor, which in turn drove a shaft, and this moved in a concentric path, about 2-4ins forward and backwards as it turned. At the end of the shaft was a box that held the cutting rod. The whole centrepiece of the machine ran on a toothed quadrant, and there were two operating handles, one of which operated the quadrant and the other that moved the cutting head back and forth on two slides.

To operate the cutter, 6 rods were used, varying in length from the starter rod at 12ins to the final rod of 5ft. The cutter pick, which was screwed to the end of each rod in turn was known as a "pig's foot". It was cylindrical in shape, with four curved points, like prongs, and was taken to the blacksmith's shop to be sharpened, when it was put in the fire, heated up and the prongs drawn out on the anvil. It was then quenched in oil to harden it. When starting to cut, the operator rotated the machine head in a semi-circle on its quadrant, moving the cutting head forward as the pick bit into the coal. As soon as the first rod had cut to its depth, the second and so on replaced it, until the fifth rod had been used. The cut then was in the form of an arc, so to square it up, the sixth rod just cut out the corners. When cutting was complete, the machine was put back on the track and moved to the next stall to be cut.

The next job was to drill the shot holes, which were drilled, 3 at the bottom of the seam, 3 at the top of the dirt band, which was present in the Ravine seam at a thickness of approx 9ins, and 3 across the top of the seam. The dirt band was fired first, and the dirt packed by the side of the roadway, as any dirt that was filled with the coal was deducted from the weight paid for in the men's wages.

The way that this was done was as follows: every week, a tub was taken at random from the pit brow and emptied. The dirt found in it was weighed and that amount was deducted from each tub that the collier filled that week. So it paid the collier to keep his coal clean as he never knew which tub was to be checked. Another reason was that in those days the colliers were allowed a load of coal as part of their wages, and this load was taken from their tally and tipped straight into the delivery truck, consequently, you got what you filled!

The top coal was always fired first and when filled out, the bottom coal fired.

When the coal had been filled out, the next job was to timber up. This involved setting a 7ft-split bar with a prop under either end. The distance between each succeeding bar was 2ft 9ins and as the working place was 10ft wide there was an 18ins gap left on either side. This was where the dirt was packed, rather like a dry stone wall. On one side of the roadway a brattice cloth was hung and this was to direct the fresh air into the heading. Ventilation in the strait workings was always on the sluggish side, the modern system is to use forcing fans and ducting, but those days brattice or "bradish" cloth was the norm. It looked a bit like heavy Hessian sacking.

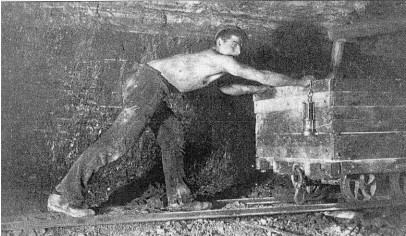

As the pillars were being worked back, when the boundary had been reached, floor heave was experienced, this being due to pressure of the strata in the waste area as the roof and floor began to converge. Sometimes the tub would only just be able to pass through, and drawers had to use a "bow" on the top of the tub to keep their fingers from getting trapped. This was a piece of iron bar shaped so as to clip on top of the tub, and provide a handle to grip as the tub was taken to the shunt.

When the collier was filling out, the drawer brought in a spare tub so that the collier could be filling whilst the drawer was taking the full tub to the shunt. This was tipped on to its side and was known as a "stonner" i.e. a standing tub. At each junction was a steel plate or "landing" where the rails stopped, and here the tub was spun round to engage it on to the next set of rails. The drawer had a set of "scotches" or lockers for the wheels, which were made from a piece of 1in round bar, tapered at one end and hooked at the other, so it could be hung from the side of the tub. When taking the full tub down an incline the scotches were used to lock the wheels. The severity of the incline was measured by the scotches needed, thus a "two scotcher" was a bit steep. Also the distance that a tub was being pushed, i.e. drawn, was measured in the amount of landing plates to be maneuvered. "Ah'm drawin' o'er five londin's" meant to say that it was a good distance from the working place to the shunt.

When the pillar was being "ribbed off" the siskol was rarely used, as the pressure on the coalface from the convergence of floor and roof was sufficient to make the coal burst off or "rate" with a little help from a hand pick. The price for this type of work was paid at a better rate than for cut coal.

There was a man who had a very lucky escape when working in a "ribbing". His name was Jem Martlew, who came from Billinge, and he was the brother-in-law of Miss E Barton, who was a teacher at Highfield School. Jem was a collier and was filling coal at the face of the rib when the roof along the whole rib collapsed. His drawer was out at the time taking a full tub to the shunt. The Ravine seam in No1 pit had a strong band of stone above the coal and this saved his life, because as the roof collapsed, it stayed in one piece and formed a triangular shaped passage through which he could crawl. He lost one of his clogs but was otherwise unharmed.

The only problem with this type of mining was that sometimes the waste would start to heat up due to spontaneous combustion, in which case the whole of the workings had to be sealed off. The Ravine rise works area was nearly worked out when I started on the haulage there, and finished soon afterwards.

There is a story to be told about Cliff Green, the undermanager who succeeded Ben Melling, concerning the pulley frame where the rope turned the corner to go down brow into the Ravine lower side. This day, a set of empties had been "tailed up" to the top of the brow, as usual, to be sent into the workings, and the chain had gone into the guard around the pulley, damaging it. I think that it was Arthur Wadsworth who was attempting to cut it free, using a hammer and chisel. Arthur was a general worker, or dataller. Cliff came up the level, "What art' doin' Arthur, gi' us th'ommer 'ere un ah'll shift it" Arthur obliged. Cliff took one swing and broke his thumb!! He did some caterwauling up and down the level, holding his damaged thumb under his arm!

About this time I enrolled at the Tech for the U.L.C.I. course in mine management, and Uncle John thought that I should get some experience in the office underground. I hated it!! I couldn't see how I could be a pitman and work in an office. I used to assist Tom Bolton with the time books. Tom did this job first thing every morning before going on to his duties as Training Officer. It was boring, -- boring!!! Filling in sheets of figures and copying out pages of names, I was fed up! I finally got away from it even though it meant shift work again.

There was one funny story to be told about this period, however. When a new lad started underground he was always put with Fred Pye to start with. As the coal came off the Yardmine belt, sometimes there was a piece with the shot hole still intact. If this piece was on top of the full tub, Fred would say to the new lad, "Tek this piece o' coal to Tommy Bowton, he wants fer t'measure th'hole" The lad would stagger into the office with the lump and show it to Tom who would say "It's OK I'm not measuring today, take it back again", by which time the lad would know that he had been had! All went well until one lad dropped the lump on the floor and it smashed into bits. That put paid to that!

The Yardmine was worked to the boundary around this time, and the men on the two faces were transferred to No2 pit where new faces had been prepared for them to work. The original faces in No1 pit had been worked in a N.Westerly direction and had gone for about 900yds. The new area was in a S.Easterly direction, but to get to it we had to go through a fault of about 50yds vertical, and tunnel under an old face.

At the bottom of the original tunnel was a 90degrees turn to the right, along a level of about 100yds and then another right angle turn to the right and a further 500yds to the old face under which the tunnels to the new area were to be driven. Belts were laid in the cross level and down to where the new tunnels were to start. The intention was that no dirt from the new tunnel was to go to the surface, so the belts from the N.W. faces were reversed and the belt drives swapped over, enabling the dirt to be sent into the old workings. The dirt from the tunnels was thus transported into the old workings of N.W.1 face and when it got there, it dropped off the belt end on to a steel plate, to be spaded into the old main gate and packed there by two men. It was packed to about 2ft from the roof to allow for ventilation. As the roadway filled up with dirt, the supports, which were 10ft larch bars, were salvaged and re-used, the belts, were shortened as the roadway filled with dirt. Not one piece of dirt from these two tunnels ever came to the surface, which was quite an achievement.

Two tunnels were driven, one for intake and one for return. The main tunnel was 11x12x9 and the return 8x7x6, both driven on arches. The tunnels were driven under the old face line and as they went under the face, the face line was packed with timber until the arches were under solid ground. I was working on the haulage on this job, bringing supplies to the tunnellers. The leading arch in the main tunnel had just got under the solid ground, when an "expert" from ICI came on the scene with the latest 6 shot exploder, and he was going to show us how to use it.

He brought with him a wooden template to show the tunnellers the direction that he wanted the holes to be drilled. All went well at first; he got 6 holes drilled in the shape of a wedge, to take out the middle of the cut. They were charged up and we retreated to a safe distance while the "expert" fired the round. What a mess! The arches had been pushed backwards and the packing timber had fallen out into the roadway. We didn't realize that when firing with this method the arches had to be braced with punch props, and as it was, just "hammerlock" struts, which were an innovation at the time, were used. Cliff Green the undermanager said "Clod it in t'pack"! The exploder was used again of course later on.

Cliff had been undermanager in No2 pit prior to the two faces finishing in No1, but had been moved to No1 to allow Ben Melling to take charge of the No2 faces, where the most coal was being produced. I don't think that the senior management had much faith in Cliff as an undermanager! To be honest I thought that he was a bit of a "prat". I had heard of his exploits from my dad who had tangled with him on various occasions. His nickname was "Why-err" from his difficulty in forming sentences. He used to walk with his head forward and his backside stuck out, and his only claim to fame was that he was a serving brother of the order of the Knights of St. John, a high rank in the Ambulance Brigade. Even at this he wasn't brilliant, especially at practical first aid.

I recall a collier, John Pendlebury, breaking his finger. He showed it to Cliff who looked at it, got hold of it, waggled it about, and promptly John fainted! He was very self-opinionated, and always thought that he knew best about everything. A clear case of "foot in mouth" every time, but more about Cliff later.

The tunnels progressed slowly, there was a conveyor installed in the main tunnel, but in the return, all the spoil had to be filled into a "dobbin" which was a wooden tub with the back removed, and a shutter fitted which could be taken out and the dobbin emptied by using a spade to load it on to the belt. In the return tunnel were the Birketts, a father and son team who came from Albert St in Newtown.

In the main tunnel were a gang of men from Lyme Pits, Ray Green, his brother-in-law Teddy Pennington, and Bill Tracy. They all came on a promise of a job on the face when it was opened up. The wages were terrible for the tunnellers, £1.50 a day, and wet conditions to boot. We used an old trench pump to take the water out, pumping it on to the belt to go out with the spoil.

I was working with an old miner, Peter Doyle, from Ashton. Peter had a chip shop, and sometimes would bring a cold fish for his snap Ugh!! I was told that they had an advertising slogan in their window: -

What do the people want? Doyle's fish and chips!

He was a great character was Peter.

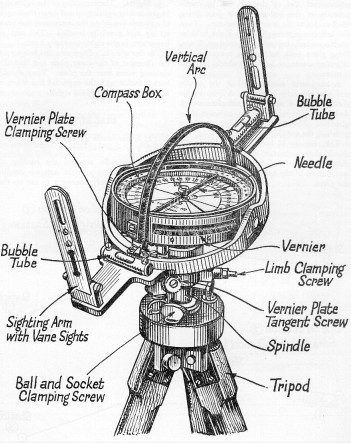

I was on the haulage job at that time, but also I was sent with various other individuals to learn the intricacies of air measuring, surveying, and dust control. This was all to do with line-management, the subject that I was learning at the Tech. When Billy Barton, the lines man (the man who was responsible for keeping the roadways on course) went on his periodic visits to "put lines on", I used to accompany him and assist. Billy had a very old type brass level, which would have been worth something today as an antique. It folded flat for easy carrying and consisted of a dial face with a compass needle that could be fixed or floating. Two pieces of brass plate were hinged on the North and South quadrants, so that they could be lifted and sighted through. There were holes in these to with cross hairs to look through. There were also calibrations for angle of rise and dip.

To set the dial into position Billy would measure off to the point that he was going to work from, drop a plumb line down, and centre the tripod that the dial sat on. The tripod also had cross-level bubbles built into it, to make sure that it was level. Billy would then mount the dial into position and proceed to mark out the new roadway or cross level, putting steel pins into the wooden bars of the roadway to hang strings from. Thus, when you put weights on the strings you were able to sight along them to keep the roadway in a straight line. I worked with Billy for a while, on and off. His brother, Tom, was a fireman on the afternoon shift. Stone's was a family pit, and generations of different families worked there.

The dust sampler and air measurer was Jimmy Picton, who came from Spindle Hillock, just up the road from the pit, and in his spare time played the saxophone in the dance band at Wigan Court Hall. When we sampled the dust, we took samples from the roof and sides of the roadways with a small paintbrush and placed them into small jars, which had labels on to note where they had been taken. This was to measure the quantity of coal dust present.

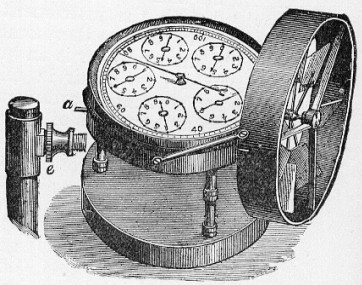

Limestone dust was spread along the roadways to prevent any chance of a coal dust explosion and when samples were analyzed, the amount of combustible dust could be measured, and remedial action taken. We also had to check the volume of air flowing and its relative humidity. This was done by use of the anemometer and the whirling hygrometer.

The anemometer was in the shape of a circle with a carrying handle, the apparatus being about 6ins across. It had a fan built into it and in the centre was the calibrated dial. This anemometer was held up in the roadway and moved around from side to side, all across the height and width of the roadway, for one minute, then by a few calculations, the volume of air flowing per minute could be ascertained. The hygrometer was in the shape of a football rattle and as it's name implies it was whirled round for a specified time, this way the humidity was calculated. I must admit, the time that I spent on this type of work was very interesting.

Whilst on with this part of my training, I was sent, along with George Ashurst, on to the night shift to go on to the Yard mine face, just for a shift. George, who was a management trainee finished up as an area safety engineer in the Western area, but died at the early age of 60, in the Isle of Man. We took a dowty prop equipped with a dial to measure the pressure exerted in tons on the roof, when the cutter had passed on its way down the face. Also we had another device to measure the convergence of the roof. George would pick me up on his motorbike to go to work sometimes, and it made a change to the pushbike.

Continued...